THIS STORY IS FEATURED IN THE 2025 NEW FRONTIERS MAGAZINE

By TYLER ELLYSON

UNK Communications

KEARNEY – At Bruner Hall on the University of Nebraska at Kearney campus, inside biology and chemistry labs humming with activity, the future of biomedical research is taking shape.

The people who work here are part of a powerful partnership that’s helped fuel student success and scientific innovation for more than two decades: the IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence program, better known as INBRE.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health and administered by the University of Nebraska Medical Center, the Nebraska INBRE program is a statewide initiative that supports faculty research, strengthens undergraduate education and builds a pipeline to graduate programs in the biomedical sciences.

Since its inception in 2001, the program has awarded more than $7 million in funding to UNK, and another five years of support is already lined up.

For faculty and students in the biology and chemistry departments – currently the only INBRE-affiliated programs at UNK – that funding is more than financial. It’s transformational.

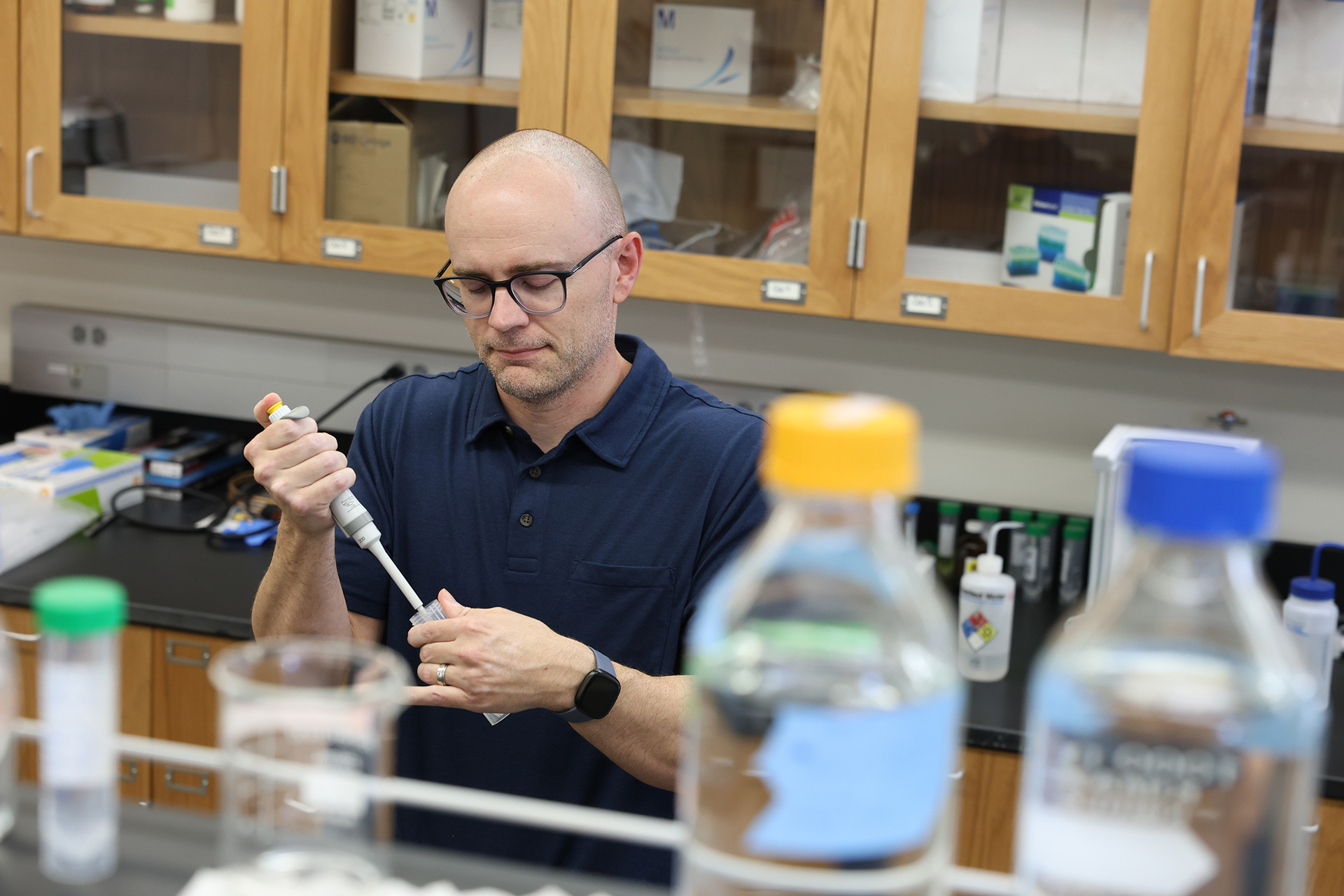

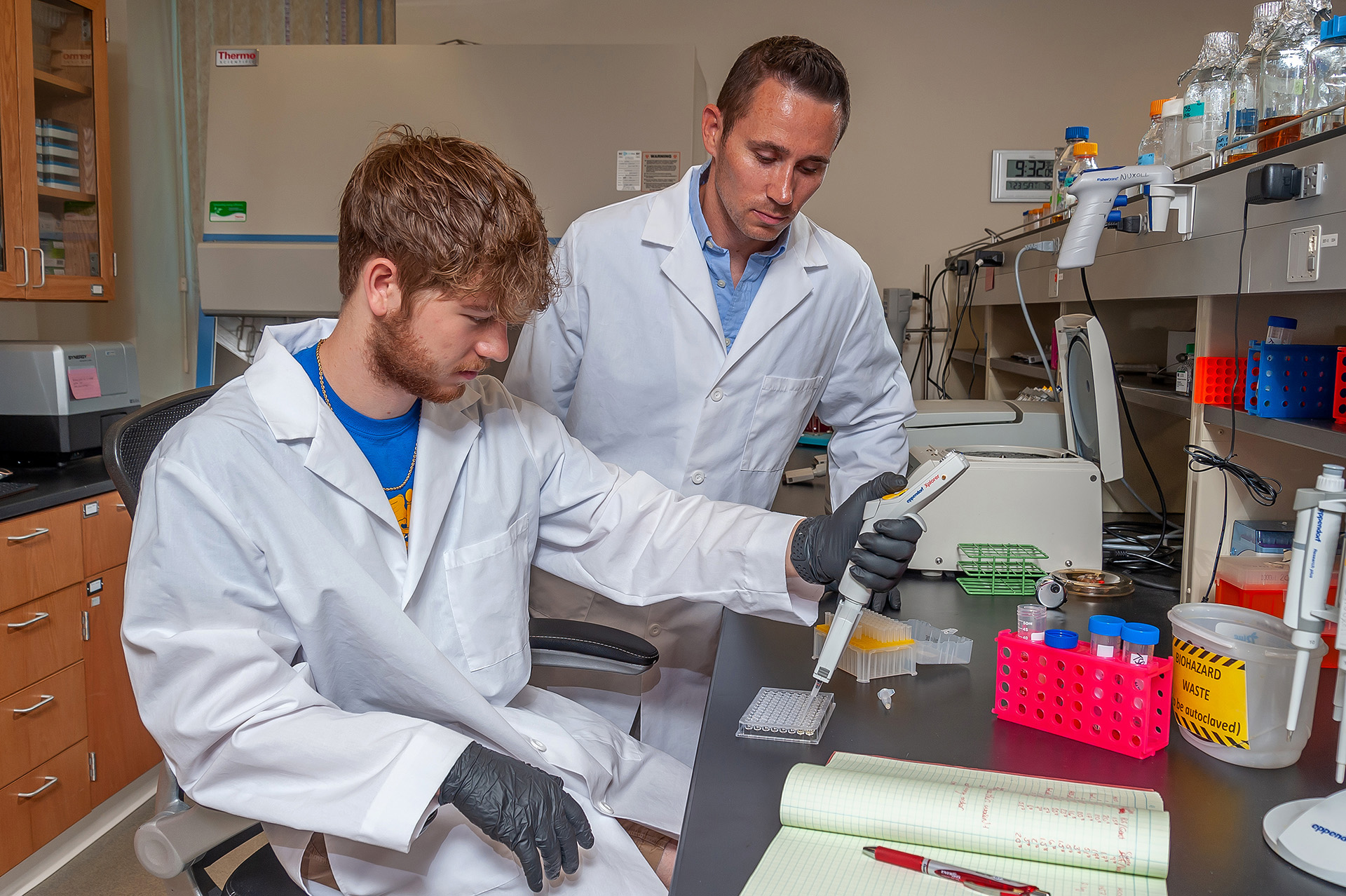

“INBRE is important because it allows us to do cutting-edge research at UNK,” said associate biology professor Joe Dolence, who’s been part of the program since 2020. “It allows us to engage our research students in lab experiences that give them incredible hands-on experiences and insight into what working in a lab will be like when they move on to graduate school. Those who enter professional school have a much better understanding of how research is conducted to bring new and innovative therapies to the clinic.”

STATEWIDE RESEARCH NETWORK

The Nebraska INBRE program connects UNK and other participating institutions with Ph.D.-granting campuses in the state, including UNMC, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Creighton University Medical Center.

It provides financial support for numerous undergraduate researchers each year, giving them an opportunity to gain hands-on lab experience both on their home campus and at a major research institution. Students are also able to attend national meetings and conferences to present their findings and network with professionals in their fields.

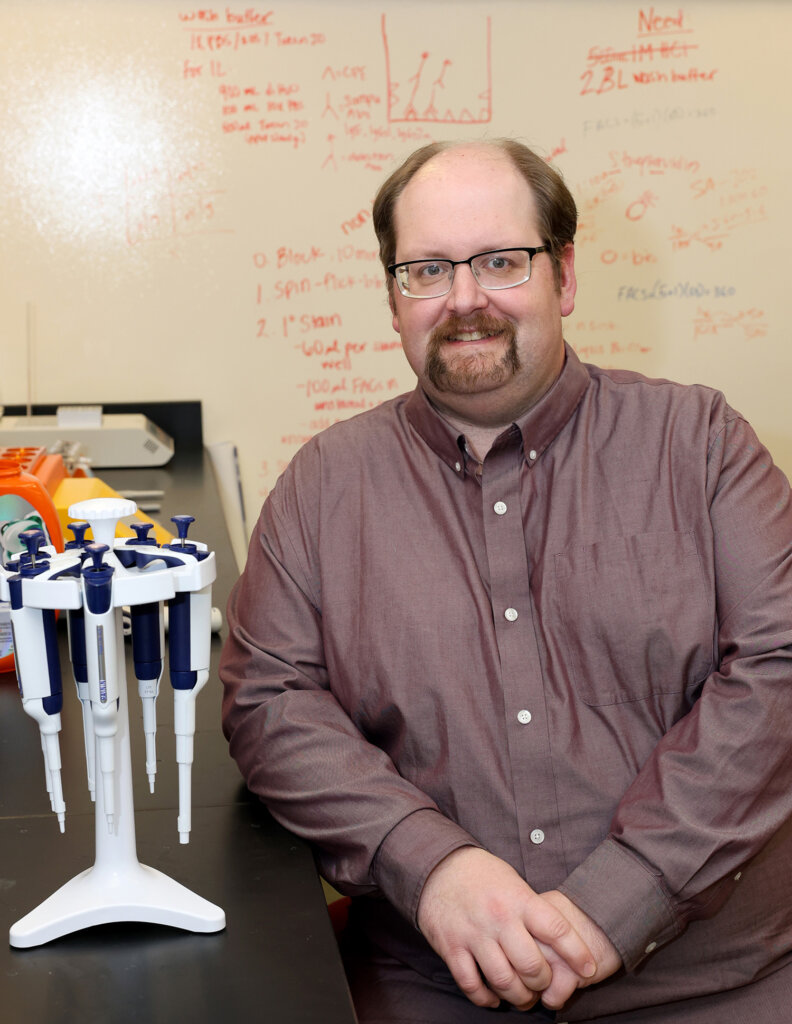

“This program allows students who have an interest in biomedical research as a career to springboard their training,” said Kim Carlson, a biology professor and assistant vice chancellor for research and creative activity at UNK. “It enhances their learning, develops their research skills and fosters their curiosity.”

Carlson has been part of INBRE since its early days, when it was still called the Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network. She’s led UNK’s involvement in the program since 2003 and continues to conduct INBRE-supported research exploring the intersection of genetics, virology, immunology and aging using fruit flies as a model organism.

“In addition to the undergraduate training, INBRE provides faculty at the participating institutions an opportunity to obtain funding for their biomedical research,” she noted. “It has provided UNK with infrastructure and equipment that we would not have if it wasn’t for our involvement in this program.”

UNDERSTANDING PEANUT ALLERGIES

Supported by an annual $45,000 grant, Dolence leads a lab that studies how the immune system responds to peanut allergens – particularly the differences between male and female responses.

“We know that twice as many women develop peanut allergies as men,” he said. “We’re trying to understand why.”

Dolence’s lab uses mice to explore the cellular mechanisms driving this disparity. He’s been studying peanut allergies since he was a postdoctoral researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

It’s a deeply personal topic since his own son, Charlie, has a peanut allergy. And it’s also a scientifically rich area of inquiry.

“We have so much left to learn about how the immune system reacts to peanut, and we know even less about how the immune systems of males and females react differently,” Dolence said. “I love the quest for an answer that has the potential to help future patients.”

Since joining INBRE, Dolence has mentored nine undergraduate researchers, most of whom have gone on to graduate or professional schools in the health and biomedical fields.

“INBRE elevates our labs to where our undergrads are thought to be master’s students, and our master’s students are thought to be Ph.D. students, when they present at regional and national meetings,” he said. “That’s a pretty big compliment. People notice the significant work we’re doing at UNK.”

CONCENTRATING THE CODE OF LIFE

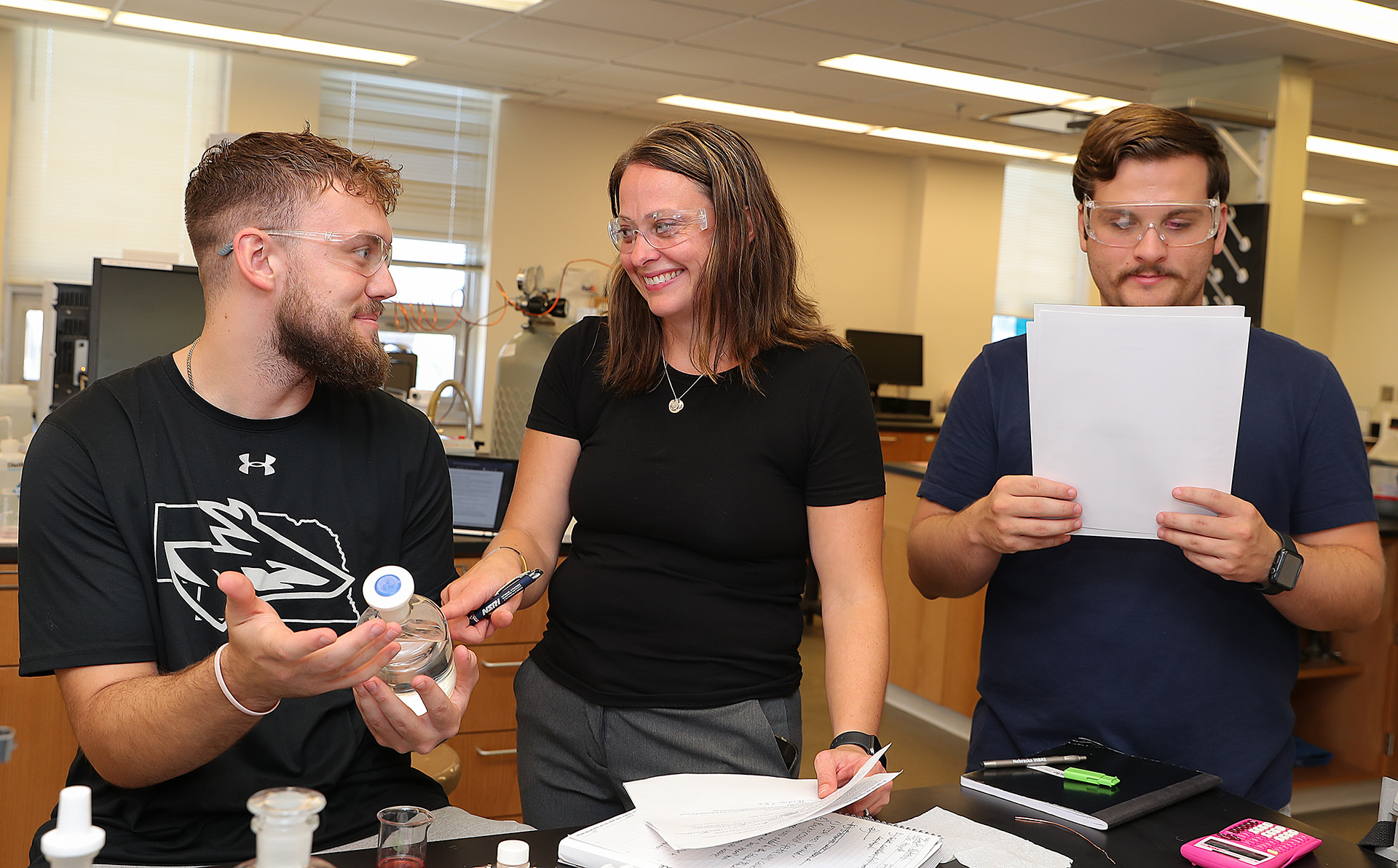

In the chemistry department, professor Kristy Kounovsky-Shafer is tackling another fundamental challenge in biomedical science: how to protect and concentrate large DNA molecules for sequencing.

Her lab has developed a novel device – designed and refined in part by her undergraduate research team – to improve DNA recovery and preserve whole chromosomes.

The work, funded by INBRE, led her to apply for and receive a separate $300,000 grant from NIH to expand the project.

“The goal of my research is to protect and concentrate whole chromosomes so they can be used in sequencing,” she explained. “This will make it easier to identify larger structural variations, which will aid in personalized medicine.”

Part of INBRE since 2015, Kounovsky-Shafer is a hands-on mentor. Her students help conceptualize, design and test new devices, often using AutoCAD software and 3D printers to bring their ideas to life.

“If my students or I come up with a random idea for a device, we design it and try it out,” she said. “For one project, we designed over 20 different devices and tested them. This is how we arrived at the current device for which we hold a patent.”

Over the past 10 years, 50 undergraduate students have worked in her lab. Many go on to graduate school and careers in health sciences or teaching. Even those not directly funded by INBRE benefit from the lab infrastructure it helps support.

“INBRE is essential because it provides students with opportunities they wouldn’t have in a traditional classroom setting,” Kounovsky-Shafer said. “They learn to think outside the box, gain independence and take ownership of their research.

“It is an amazing program that has helped shape the research culture at UNK.”

FOSTERING FUTURES IN SCIENCE

Beyond the labs and data, INBRE’s greatest impact may be in the people it empowers. The program helps talented undergraduates across Nebraska – many from rural areas – discover their potential as scientists and pursue careers they might not have otherwise considered.

It also affirms the power of public universities like UNK to lead high-quality research and inspire innovation.

“UNK is a special place to do undergraduate research and mentor students,” Dolence said. “The work we do here, and the way we do it, is special. We have a gem in the center of Nebraska that needs support to keep growing. INBRE is a big part of that.”

With continued investment and passionate faculty at the helm, that gem is poised to shine even brighter.