By ERIKA PRITCHARD

UNK Communications

Jamie Vaughn tightly crossed her arms as she slowly crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

Wearing a T-shirt, hooded sweatshirt, jeans and sneakers, the University of Nebraska at Kearney sophomore carefully moved across icy patches on the bridge’s narrow walkway.

Though it was mid-January, she expected it to be warmer in the Southern U.S. But unseasonable weather hit the region the day before Vaughn’s visit, bringing a skiff of snow and high temperatures in the lower 30s.

As she looked across the murky water of the Alabama River to the left and vehicles passing along U.S. Highway 80 to the right, Vaughn thought about how foot soldiers from the Civil Rights Movement must have felt nearly 60 years ago as they marched across the bridge, named after a Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader.

Vaughn imagined the chaos that ensued on March 7, 1965, now known as “Bloody Sunday,” when about 600 people, demanding voting rights for Black Americans, set out to walk 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. But unlike the quiet and undisturbed walk last month, the civil rights marchers were met at the end of the 250-foot bridge with violence. They were teargassed, chased and beaten by state and local law enforcement officers on horseback and foot.

“I tried to put myself in those people’s shoes, like, ‘What is this for?’ It changes everything. It’s not just a bridge,” Vaughn said.

Finally, on March 21, 1965, which was their third attempt, several thousand civil rights marchers successfully left on foot from Selma and arrived at the steps of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery four days later. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on Aug. 6.

One of the marchers fighting for his rights was 17-year-old youth leader and foot soldier Charles Mauldin. Now in his 70s, Mauldin invited Vaughn to walk next to him as they crossed the bridge on this cold January day. Fifteen other UNK political science students, their professor and pre-law adviser Chuck Rowling and University of Nebraska College of Law Associate Dean Anthony Schutz followed two-by-two behind them.

“I can’t stop thinking about that bridge and that moment. I just think that opportunity, you don’t get that anywhere,” Vaughn, a Gretna native, said.

The experience in Selma was part of a new experiential learning opportunity within the Kearney Law Opportunities Program (KLOP) that took students to Georgia and Alabama during the January intersession. And it was part of a new course – “The Politics and Law of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement” – developed by Rowling, who had been on four similar trips to the Southern states and spent 10 years developing the class.

Rowling created the curriculum to not only teach students about this important part of American history but to also help them become more educated and well-rounded citizens as they prepare for careers in law.

“So much of the struggle for civil rights is related to legal action, court cases and changing laws,” he said. “If you want to make change and you’re a lawyer, you’re doing so within the context of the law. So, it doesn’t matter if it’s civil rights or anything else, understanding those dynamics and that process is crucial to all that you do as a lawyer.”

Students read about and discussed these topics before visiting places where the movement began. Between Jan. 12-16, they met with eight different activists, scholars and lawyers and explored Atlanta, Georgia, and communities in Alabama – Tuskegee, Anniston, Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma.

Ella Ferguson, a sophomore from Springfield, said learning about the Civil Rights Movement in the South, rather than a textbook alone, made the history more real to her.

“It really brings to life the events that happened because we’re right there where they occurred, and we really can picture the violence that occurred against the activists,” she said.

Firsthand experiences

The students and faculty started their tour in Atlanta. In the morning, they hiked Stone Mountain, where a Confederate memorial depicting Jefferson Davis and Civil War generals is etched. When they reached the top, they had a vast view of Atlanta.

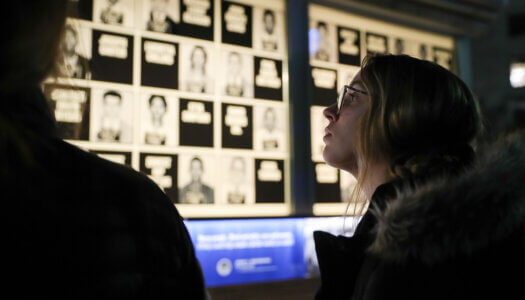

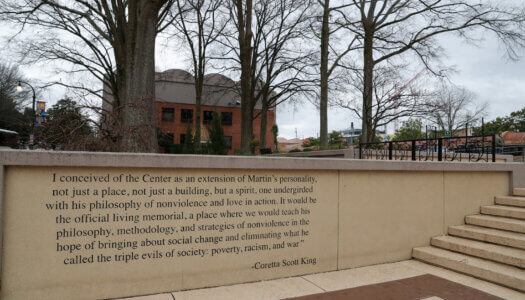

Then they walked through the rain along Auburn Avenue, a street that was once a center of African American success. They saw the tomb where Martin Luther King Jr. and wife Coretta Scott King are buried and Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King co-pastored with his father. They also met with Hank Stewart, the 2016 4th Congressional District of Georgia poet laureate, and finished the day looking at exhibits at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights.

One exhibit particularly affected Vaughn. She learned that Alabama was the last state to overturn its ban on interracial marriage in 2000. Her mom, who is white, and her dad, who is Black, married in Missouri in 1999. Had miscegenation laws been in place locally at that time, she said she wouldn’t be here today.

“I never thought about that before, so it changed the course of the trip for me mentally,” Vaughn said.

The following day, the students took a bus to Alabama. On the way to a short stop in Anniston, they reflected on the Freedom Riders, who fought for desegregation of interstate travel. Outside Anniston on May 14, 1961, one bus was firebombed and fleeing passengers were beaten by a white mob.

The UNK group then traveled to Tuskegee to tour historical sites before meeting with civil rights leader Bernard Lafayette Jr. and his wife Kate. As the group ate gumbo in the basement of Lafayette’s church, he shared stories from his past and signed copies of his memoir, “In Peace and Freedom: My Journey in Selma.”

Lafayette ended the evening with songs he and other Freedom Riders sang in a Jackson, Mississippi, jail.

“We were on the third floor of the city jail. So, we could see the highway and we could tell when the buses were coming,” Lafayette told the UNK group. “So, we made up a song. It goes like this, ‘Buses are a comin’, oh yes ….’”

The Riders continued with different versions of the song. Next, he sang, “Better get you ready, oh yes ….”

They added lyrics as jailers threatened to take their mattresses and toothbrushes.

“You can take our mattress, oh yes …,” Lafayette sang. “You can take our toothbrush, oh yes ….”

Finally, Lafayette belted, “We will keep our freedom, oh yes.”

The evening with the Lafayettes was a highlight for UNK senior Braden Peterworth.

“That guy has seen it all. He’s just a hero who influenced the United States in ways other individuals I’ve met couldn’t even dream of,” the Sutton native said.

The next day in Montgomery, the students and faculty walked from the Alabama Riverfront down Commerce Street to Court Square, the same path Black slaves were led down to be sold. The UNK group then turned the corner and walked up Dexter Avenue to the State Capitol, following the route marchers from Selma took in 1965.

Before reaching the Capitol steps, they stopped outside Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where King had once preached. As Terry Anne Scott, director of The Institute for Common Power, spoke to them about the history of the city via Zoom, vocal music poured out the church doors during its Sunday service.

Common Power Associate Director for Organizational Support David Domke then finished the discussion via video from the Capitol steps. While he spoke, students peered at the towering Confederate Memorial Monument in front of them.

Also in Montgomery, students visited the Legacy Museum, which tells the history of racial injustice – from slavery to the Jim Crow era to today’s mass incarceration. In Rowling’s opinion, the museum provides the most comprehensive view of the subject.

“For me, it’s that and the Holocaust Museum as the most powerful museums that I’ve ever visited in the United States,” he said.

The following day – Martin Luther King Jr. Day – community leader and filmmaker T. Marie King led a tour of Birmingham’s civil rights historic district. The district includes the A.G. Gaston Motel, where King and other African Americans stayed during visits to the city, as well as Kelly Ingram Park and the 16th Street Baptist Church, the center of the 1963 Children’s Crusade that influenced the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On the final day, students crossed that infamous bridge in Selma and toured other historical sites with JoAnne Bland, who was 11 when she marched on Bloody Sunday and later to Montgomery. The students ended their day in Montgomery, talking over dinner with a young Alabama ACLU lawyer, Laurel Hattix.

“To talk to someone who is not much older than these students who are on this trip and is actively working on these issues in Alabama and beyond was a really powerful experience,” Rowling said. “She spoke the language of these students in ways that I can’t.”

Continuing their journey

In Rowling’s eyes, this experience was impactful for students on many levels, making it a success. He intends to continue providing this opportunity for KLOP students every other year.

“It was a jam-packed trip. To me, that’s the only way to do something like this. It was less pleasure and more experience, and we explored some tough topics and issues,” Rowling said. “Students’ reflections all spoke to one central theme, which was what made this trip so amazing – the people we met.”

Some of the students expressed interest in activism. Vaughn and four of her peers have applied to a summer online learning program, Action Academy, facilitated by Seattle-based Common Power.

The experience also affirmed Vaughn’s desire to eventually go into public service law.

“I think about the Legacy Museum and about how it showed the disproportionate number of persons of color in prison versus white people. That’s what I want to work toward and fix a little more,” she said.

You can do this kind of work anywhere, Rowling noted.

“Everywhere you go, there are issues related to civil rights,” he said. “I think, at minimum, many of these students have thought about, ‘How can I address problems related to marginalized communities in rural Nebraska?’”

Peterworth graduates this spring and plans to start law school in the fall. He’s interested in the University of Nebraska College of Law’s new Innocence Clinic, which gives law students the opportunity to represent people who may have been wrongfully convicted of a crime.

He’s also thinking about the difference he can make as a lawyer and leader in rural Nebraska.

“One of my favorite quotes from the poet Hank Stewart, who we met with at the beginning of our trip, is, ‘It’s our time, it’s our day, and if we don’t make a change, it’s our fault,’” Peterworth said.

PHOTOS BY ERIKA PRITCHARD, UNK COMMUNICATIONS