By JAN TREFFER THOMPSON

By JAN TREFFER THOMPSON

From 30,000 feet above the Great Plains, you can’t actually see political boundaries. Just hills and valleys, fields and streams.

But when people look at environmental issues in “flyover country,” historian David Vail says, too often all they see is a battle line with producers and their farm chemicals on one side and environmentalists on the other.

Vail has a different perspective.

The University of Nebraska at Kearney assistant professor focuses on life at the ground level, where technology and agribusiness coexist with a concern for the environment – not just within a region and its communities, but within the people themselves.

“Rural people have their own views on conservation. They’re not the same views all the time that we are sort of familiar with, but they matter. And they matter a lot. And people who use the land also care a lot about it,” he said.

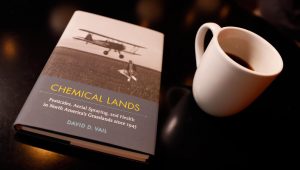

That focus has informed Vail’s research and writing, including the 2018 book “Chemical Lands: Pesticides, Aerial Spraying, and Health in North America’s Grasslands since 1945.” The book looks at how the spread of aerial chemical application affected not only agribusiness, but also environmental debates in the Great Plains.

“After World War II, spraying from the skies in the grasslands turned pilots into scientists, airplanes into farming tools, and pesticides into poisoners as well as protectors,” Vail writes.

In researching “Chemical Lands,” Vail looked closely at that evolution. What he found wasn’t a story about producers concerned with putting more money in their pockets, ignoring the warnings of environmentalists. It was a story about weed scientists, farmers and pilots who were concerned with precision. They field-tested new science and technologies as they weighed threats against benefits. The book shows how their efforts helped create national standards that govern the industry today.

The idea that people who work the land can also love it may surprise some today who see agriculture as the enemy of conservation, Vail said. But to him it seems natural.

LOVE OF NATURE

LOVE OF NATURE

On the walls of Vail’s office in Copeland Hall are framed reproductions of Works Project Administration posters from the 1930s – one for Crater Lake National Park and another for Glacier National Park. They’re places Vail knows well. He keeps the posters around to remind him of the nature he loves and the way it’s been used for entertainment, production and inspiration.

“I love the national parks. I grew up going to Crater Lake National Park every year when I was younger, and that really changed me to get really excited about this, really impassioned for this stuff,” Vail said.

From Southern Oregon’s Rogue Valley, Vail grew up hiking, camping and mountain biking. He learned the importance of stewardship of the land from a family with deep connections to it (his great-great-grandmother was Klamath, a tribe that now lives on Oregon’s Umpqua Reservation) and from regular treks into the wilderness with his father and grandfather.

“My grandpa was a car mechanic, but he loved the wilderness, so we would go camping and he would explain the ecosystems that we would see – the relationship between ranching and farming in rural Oregon and the deer populations and timber. He worked on and off for timber companies that, even back in the 1950s, pursued more of a conservation ethic in timber,” Vail said.

Living in a state with regular public debates about the timber industry and preservation of public lands, Vail saw how producers felt about the land they worked.

“A lot of my friends and their dads, or people they worked for, their families were farmers. They talked a lot about conservation. They had a different language about it. But it wasn’t just about inputs and outputs and producing. They talked about love of the land and stewardship, thinking about stewardship. So, they may be fishing in a local pond, but they’re also concerned about the fishing ecosystems of that pond, as it compares to how they produce on the land nearby,” Vail said. “All of that shaped how I see environmental history and agricultural history now.”

MANAGING RISK

MANAGING RISK

Every summer, Midwestern skies fill with the drone of small aircraft engines as crop dusters dip-rise-turn, dip-rise-turn, spraying blankets of (usually) insecticide over fields. Today, regulations govern how much chemical should be sprayed per acre. Pilots have precision controls and guidance systems that make sure they spray their target fields, and nothing else.

It wasn’t always this way.

Though aerial application of farm chemicals began in the 1920s, industrial farming techniques didn’t see widespread use until after World War II. Then, new herbicides and insecticides came on the market, promising more effective control of the weeds and bugs that destroyed crops.

In his book, Vail shows that when these chemicals came on the market, Midwestern farmers and ag pilots recognized that misapplication presented risks to the health of land, animals and people. They took an active role in testing the science. Working alongside university scientists and Extension specialists, they planted test fields, ran experiments and altered or created new equipment to figure out how they could manage the risk.

Something Vail came to understand was that

agricultural spraying developed with the help of many regional influences.

“Not just the industry involved, but the plane itself is a manifestation of regional influences. Culturally, technologically, how booms were designed, how early pilots concocted their own spray planes,” he said.

An example of this innovation is how spray planes carry the chemicals. At first, Vail wrote, pilots built their own metal tanks. But corrosion and leakage were big problems. Some pilots tried cloth or rubber linings inside the tank, which helped, but leaks continued until double-lined tanks were created. They also installed agitators, air vents and hydraulic pump systems.

Some innovations worked, others didn’t. Eventually, the industry developed standards and the government passed regulations controlling the use of agrichemicals. What’s most interesting to Vail is how much producers, pilots, scientists, Extension services and lawmakers worked together to create those controls in what he terms a “field-view” approach to agricultural science.

One moment Vail writes about is the Environmental Protection Agency’s initial standards for application of dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Known commonly as 2,4-D, the herbicide was commonly sprayed in low volumes. The EPA set the standard for minimum use (the minimum amount one could safely use on an agricultural landscape) relatively high, Vail said, giving producers more latitude.

“The pilots all wrote letters to the EPA saying, ‘This is way too high. You’re actually setting a minimum that will not only be deadly to fields, but also it would be extremely expensive,’” Vail said.

Eventually, the standard was lowered. Those ag sprayers were actually asking the government for stricter regulations.

“The pilots had a mindfulness that I found interesting, but also important, that they have a sense of this that’s beyond the excitement of flying an ag plane, or the lucrativeness of their industry,” Vail said.

ROAD TO AG AVIATION

ROAD TO AG AVIATION

Vail’s research actually began during his graduate work at Utah State University, where he saw cooperative regional influences in the history of a water conservation district. He went to Kansas State University hoping to research water issues in the Great Plains and work with professor Jim Sherow, who’s known for his scholarship on water issues.

Sherow gave him some unexpected advice.

“I showed up at KSU, and my adviser said, ‘A lot of people are doing water topics, David, but I have a colleague who came across all these pesticide files that no one’s ever looked at.’”

Once Vail saw the files, he realized he had a rare opportunity. The Great Plains was an obvious place to research pesticide use, and little research had been done.

Even less research had been published on aerial spraying, which Vail quickly noticed played a central role in the spread of pesticide use. Some pilots had written about their experiences, and he found one book about aerial spraying in the South. A historical look at how spraying affected agriculture in the Great Plains didn’t exist.

“Agricultural aviation plays a significant role in how Great Plains agriculture happened, not just in Kansas or Nebraska but in the region, from World War II on,” he said.

Vail found a professional group for agricultural pilots and attended their meetings. He was thrilled to find full transcriptions of the North Central Weed Control Conferences, which had drawn together people from all corners of agribusiness annually since 1944 to share their data, insights and concerns.

The transcripts painted a picture of an industry that was self-regulating. People in agribusiness worked with scientists and the government to create standards and regulations.

Those unexpected partnerships, though, wouldn’t last.

“There were Great Plains pilots right there at the table, informing that shift,” Vail said. “The politics are sort of light-years apart by the ‘60s and ‘70s. I do sort of look at the pre-‘Silent Spring’ era and the post-‘Silent Spring’ era.”

SILENT SPRING

When biologist Rachel Carson wrote “Silent Spring,” her seminal critique of chemical agriculture, she was fighting cancer. When Vail read the book for an American environmental history graduate course, his mother was facing her own battle with the disease. He said that was just one reason he found Carson’s impassioned, science-based treatise impactful.

“For me it was thinking about my relationship to the larger environment, how landscapes are made and remade, and the consequences of what that means, and thinking holistically about the environment, and all of that happened for me when I read ‘Silent Spring,’” he said.

The book pairs a solid scientific approach with elegant prose about the environment, Vail said. When it was published in 1962, Carson’s status as a female scientist writing for a general audience caused almost as much controversy as her critique, which included Carson’s argument that ag chemicals put everyone’s health at risk.

“A lot of response overlooked that she never called for a ban on chemicals. She just said these things are a lot more dangerous than we thought,” Vail said.

Any historical research into pesticide use would have to consider the effect of “Silent Spring,” Vail said. Putting his personal admiration for the book aside, Vail saw how its ideas helped quash those “unexpected partnerships” he had seen at work in agribusiness and polarized the debate over chemical use.

The book prompted President John Kennedy to create a commission to study the use of one pesticide, DDT. Testifying before Congress, Carson went into detail about the risks to ecosystems and humans. She directly criticized aerial application, charging ag pilots with using the toxic chemicals irresponsibly.

It was true, Vail said, that rogue pilots existed who didn’t follow best practices and, in some cases, even mixed their own bootleg farm chemicals, selling them to farmers at a discount. These sprayers were primarily in the South, but Carson’s critique covered the whole industry. Great Plains pilots took offense.

“They were pursuing precision and standardization in a way their Southern colleagues, if we can call them that, were not,” Vail said. “They felt they were lumped into this larger group and cast aside as the violators of the environment, when they saw themselves as the protectors, recognizing that these things are dangerous, and here’s what we’re trying to do to mitigate the risk.”

As one pilot Vail interviewed told him, “We woke up one morning and we were on the wrong side.”

With environmentalist voices raised against farm chemicals, people in agribusiness went on the defensive. The atmosphere changed, Vail said; instead of cooperatively working to set appropriate regulations, farmers and pilots started looking for ways to protect their industry.

Chemical companies reacted to the changing environment by changing their sales pitch. “They figured out the language,” Vail said, and filled their marketing with the message that chemicals protected the land, crops and agriculture from the weeds and bugs out to cause harm.

BEYOND THE CHEMICAL LANDS

BEYOND THE CHEMICAL LANDS

Since publishing “Chemical Lands,” Vail has added book signings and public readings to his work as a scholar and teacher. He’s also started work on two new book projects.

One of those projects will look at the role of environmental hazard science in the Great Plains and rural Midwest, especially during the Eisenhower administration. Another, co-authored with a colleague at the Henry Ford Museum, will show public historians how they can integrate environmental history into exhibitions.

Vail also engages in public history. He’s active as a writer, reviewer and consultant for exhibitions. He also hosts “This Month in Agricultural History,” a monthly spot on KRVN Radio.

“I try to connect to what Nebraskans and other people in the Great Plains would enjoy hearing about,” he said, adding that community engagement is an emphasis for UNK’s Department of History.

“For me, it’s exciting to be part of a department that’s so vibrant in its efforts to reach out to the community,” Vail said. “We care about how what we’re doing connects to what the community needs, and thinks it needs.”

That community includes Vail’s students. He advises two student groups, the Sustainability Group and UNK’s chapter of Phi Alpha Theta, the history honors society, alongside his teaching duties.

“The teacher-scholar model that UNK embraces has been crucial for the inspiration to ask new questions about my own research that I may not have come to on my own,” Vail said, adding that he’s enjoyed being able to connect his scholarship to his courses.

Vail has developed courses on agricultural history, the history of science and technology, war and the environment while at UNK. He brings agriculture and environmental history into his introductory American history classes, such as telling students about the first wind erosion tests for tree breaks that were done in Nebraska.

Classroom work can even connect specifically to his research, Vail said, since students from rural areas often have their own opinions about farming and chemical use.

When a student’s comment or question pushes Vail in a new direction, it echoes the “unexpected partnerships” that have been the focus of his research.

“One of the lessons, again, is that people must have unexpected partnerships and work together to figure this out. Agriculture health and the health of the larger environment aren’t these separate things that can be argued about. They’re intertwined,” he said.

It’s a lesson Vail said would be useful if applied in today’s national debates.

“Some of the most conservation-minded people are the same people who use their land. They’ll be the first ones to protest if their fields are mis-sprayed. They’re the first to say we need to have some sort of regulation to make sure herbicides and insecticides aren’t free-flowing into our river,” Vail said.

But in today’s politicized and polarized national climate, people are more likely to dig into their own trenches than cross imaginary battle lines.

The cooperative partnerships Vail studies and writes about offer an alternative.

“This history helps us understand where we can go. Where people went once.”

DAVID VAIL

Title: Assistant Professor, History

College: Arts and Sciences

Education: Bachelor of Arts, history, minor in political science, Southern Oregon University, 2004; Master of Arts, history, Utah State University, 2006; Ph.D., history, Kansas State University, 2012.

Years at UNK: 3

Career: History instructor, Kansas State University, 2008-12; Public services archivist, Kansas State University, 2013-16; Board member, Kansas Humanities Council, 2013-16; Assistant professor of history, University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2016-present.

Family: Wife, Rosanna Vail, communications assistant at UNK eCampus and managing editor for the Human-Wildlife Conflicts journal.

Hobbies/Interests: Mountain biking, hiking, national parks, collecting U.S. Department of Agriculture agricultural yearbooks, coffee connoisseur, exploring natural areas with my dog Gingerbread, getting nostalgic with 1990s throwback games on modern video game consoles.

Honors/Awards: Eisenhower Presidential Library Research Travel Grant, 2017; Hamaker Summer Faculty Fellowship, UNK Department of History, 2017; Michael Schuyler Award for Excellence in Teaching, UNK Department of History, 2017; Visiting Humanities Scholar Grant, Illinois College, 2018.

Areas of research/specialization: Environmental and agricultural history, science and technology, the Great Plains and public history.

Courses taught: Graduate courses: Warfare and the Environment in the 20th Century, American Environmental History, Agricultural History, History of Science and Technology, History of the Great Depression and American Interpreted. Undergraduate courses: American History.

Recent Published Book:

– “Chemical Lands: Pesticides, Aerial Spraying, and Health in North America’s Grasslands since 1945,” 2018.

Recent Published Articles:

– “Farming by Rail: Demonstration Trains and the Rise of Mobile Agricultural Science in the Great Plains,” Great Plains Quarterly 38, 2018.

– “Sustaining the Conversation: The Farm Crisis and the Midwest,” Middle West Review: An Interdisciplinary Journal about the American Midwest 2, 2015.

– “Kill That Thistle: Rogue Sprayers, Bootlegged Chemicals, Wicked Weeds, and the Kansas Chemical Laws, 1945–1980,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 35, 2012.