By KIM HACHIYA, UNK Communications

Consider this situation:

You are the boss of a highly educated, dedicated professional who is good at her job, and in whom you have invested time and resources. But a recent culture shift in your organization has upset her apple cart in ways that make it hard for her to succeed like she once did.

She was a happy, early-career professor who worked to earn her master’s and doctoral degrees to teach principles of management, business ethics, business communications and accounting at your small Midwestern college. She has been perking along in her discipline, focusing on teaching – a task at which she excelled. But the college has become part of a larger state university system. And a new campus chancellor is realigning the new university’s mission with more emphasis on scholarly research as an indicator of faculty productivity.

Suddenly, your professor is not so happy. She wants to teach, not do research. As her supervisor, what options might you suggest to help motivate her to success? What best management practices should you employ? Discuss.

This is a brief start to a case study, a now-familiar tool used in many classrooms to help students apply knowledge to real-world problems. Kay Hodge, professor of management at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, is a recognized expert in the field of case writing and using case study in the classroom. And as you may have guessed by now, she was that early-career faculty member in the early 1990s who was not excited about having to develop a research portfolio as part of her teaching duties.

“I dug in my heels so hard, you could have plowed a field with them,” Hodge said. She joined the faculty 32 years ago, when UNK was Kearney State College. “Teaching was my niche. I didn’t want to do research.”

Learning Outcomes

Learning Outcomes

In 1993, Hodge and a few other colleagues went to a conference at Northwest Missouri State University. Truth be told, her department chair “encouraged” her to attend, she said. The conference was on the emerging, and then somewhat maligned, discipline of case study pedagogy – using real world cases/situations/problems in the classroom to help students learn to apply knowledge or make informed decisions.

It was not love at first sight, Hodge said. But it was an eye-opening experience because she found the collegiality among those in attendance to be inviting and stimulating. And she started to see a way to become more engaged in research through the development of the discipline of case writing. Now, she is a well-recognized expert in the field who has edited the discipline’s leading journals, been president of its scholarly society, and in summer 2016 hosted the society’s annual workshop on the UNK campus.

Case writing is not just coming up with a problem for students to dissect. A good case requires research into many aspects of the situation and usually includes observations over time with an eye toward holistic interrogation of a situation. But the real heavy lifting – the intellectual achievement – is developing and writing the case note, Hodge said. This is the document in which the instructor learns how to use the case: the learning outcomes that students should achieve; what principles and theories the case demonstrates and how they can be applied to the case; how to analyze various aspects of the case; and how these theories and principles have held up over time.

“The note brings the theory to a head and explains why teaching the case is important and relevant,” Hodge said. “The beauty of the method is that it brings the theories we teach in textbooks into real life.”

When Hodge sets out to design a case study, she first thinks about what she wants students to learn. Then she creates the learning outcomes. Finally, she writes information about the case. The teaching note describes which theories might be applied and how the case might prove, or disprove theories.

For example, Hodge described a few principles or theories she might use when writing a case focused on business ethics:

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a pyramid with five levels with physiological needs at the base, and in ascending order safety, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization are realized.

- Justification of actions, such as utilitarianism – the greatest good for the largest number of people or deontology, the duties and obligations of the action rather than the consequences.

- Social responsibility: do businesses have an ethical obligation to give back to society? Is the sole duty of business to make a profit? At what cost? Do we care if there are negative consequences? Is there a scale of negatives in which a little bit is OK? Where’s the line in which a consequence becomes unacceptable?

- Stakeholder theory: Espoused by Edward Freeman, this looks at how businesses create or destroy value for their various stakeholders, who include customers, stockholders, clients, employees, communities and financiers.

If the case is focused on management, she would look at various theories of management, human psychology and behavior, leadership traits and practices, and other principles and theories.

Changing Attitudes

Changing Attitudes

Case study can be used across many disciplines, not just business, she notes. While law schools have employed case studies for generations, business schools, medical schools and disciplines such as history, philosophy and science find applications.

Case methodology was once denigrated, she said, with some in academe seeing it as intellectually lazy. It’s taken hard work by people such as Hodge and others in groups such as the Society for Case Research, of which Hodge was president in 2010-11, to lift the discipline’s profile and reputation.

“We educated deans and others as to the value of case methodology as a legitimate pedagogy. We just kept taking our argument to them and showing examples of why this method works. It is definitely a pedagogy based on scholarship and research and is a perfect vehicle for new faculty to begin research.”

Do students like case studies? Yes and no, Hodge said.

“When I used to just teach with the ‘book,’ students would glaze over,” she said. “But with a case, at least two-thirds of a class will find the case relevant and interesting. Today’s students are different than we were. We accepted ‘sage on the stage.’ But students today expect to be included in their educational process, that it be interactive and relevant. They want to know ‘How are we going to use this? How does this apply to me?’ You know, real life is stranger than fiction, so there is no end to interesting cases.”

However, there is that one-third who don’t enjoy case study pedagogy, she noted. These are the students who are less engaged, and they just want to know the answers in black and white/true-false/multiple choice; they are less likely to be critical thinkers, she added.

Students tend to really enjoy cases involving ethics, she said. Cases that require more thinking about management strategies or pulling multiple parts of an organization together tend to be less popular. Short cases that can be examined over one or two sessions also are popular, she said. Students either may orally discuss and present findings or write research papers.

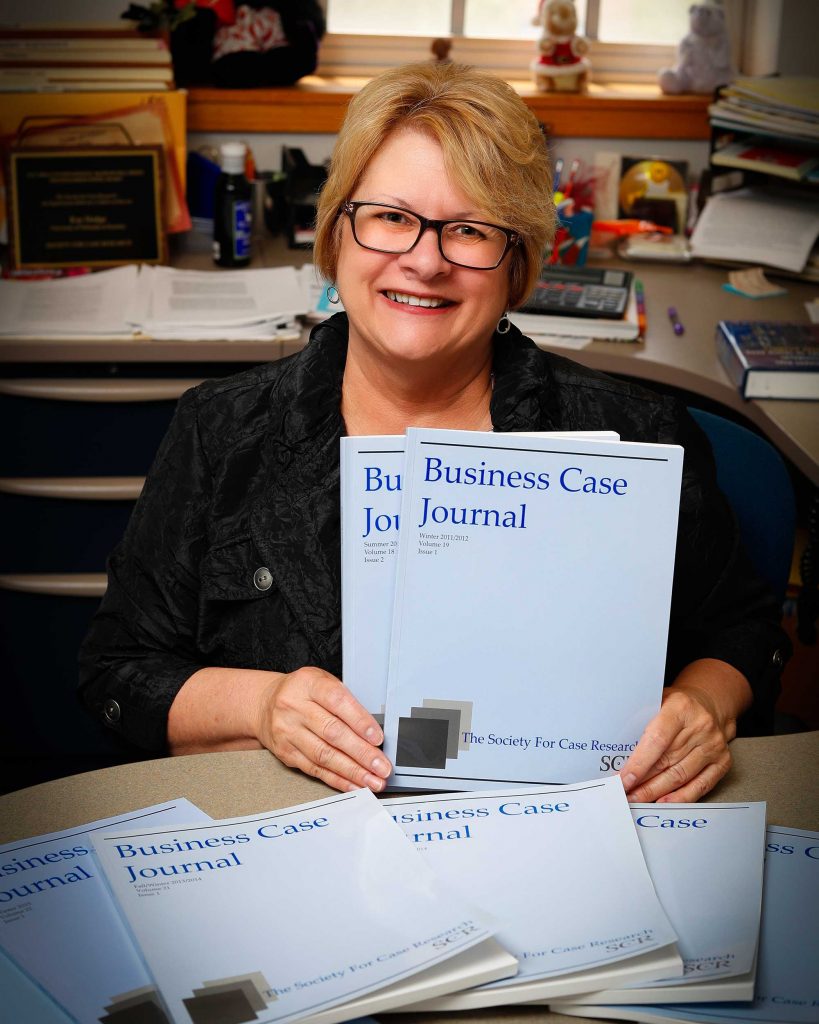

The Society for Case Research publishes three journals; Hodge edited two of them.

She edited the society’s leading and most prestigious publication, Business Case Journal, and Journal of Case Studies (formerly titled Annual Advances in Business Cases). She recently turned over the reins of Business Case Journal, which she oversaw from 2004-15. The society’s third publication, Journal of Critical Incidents, tends to publish shorter explications of single incidents. Some examples of case topics could include how an auto company handled a particular defective auto recall or how a restaurant chain managed a food poisoning outbreak.

The society’s summer workshop, hosted in July by UNK’s College of Business and Technology and organized by Hodge, included two tracks: helping writers refine and complete a case study that is in progress so it can be submitted to a journal; and a “boot camp” where writers with a germ of an idea learned how to research and sharpen their ideas and write that critical teaching note.

Hodge notes that the Business Case Journal accepts only about 10 percent to 13 percent of cases submitted for review. Journal of Case Studies accepts 25 percent to 30 percent of submissions. Attendance at the workshop does not guarantee acceptance, Hodge said. A case writer’s intellectual property is protected, she said, because when a case is accepted for publication by a journal, it is released through McGraw-Hill and other publishers, who ascertain that the people requesting the cases and accompanying teaching notes are actually professors using the materials for academic purposes. The publishers sell copies of the case and the important teaching note.

Hodge is nearing the end of a long and satisfying career at UNK. She has no regrets about attending that workshop back in 1993.

“In case writing, it’s not about the destination, it’s the journey,” she said. “I really fell into case writing sort of by accident. It wasn’t a planned or designated journey. Yet now, I cannot picture myself doing something like researching something that just doesn’t matter. I feel like what I have done matters.”

What is learned from the above case?

Great teachers are always learning. Finding relevance and meaning leads to satisfaction, self actualization.

Listen to your chair. And listen to your heart.

Kay A. Hodge

Title: Professor, Department of Management

College: Business and Technology

Education: Bachelor of Arts, Education, Kearney State College, 1981; Master of Science, Education, Kearney State College, 1983; Ph.D. in Administration, Curriculum and Instruction, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1988.

Years at UNK: 32

Career: Payroll clerk, Gibbon Packing Inc.

Family: Daughters Amanda Skala of Gibbon, Stephanie Kee of Gibbon and Hiliary O’Neill of Kearney.

Hobbies/Interests: Reading murder mysteries, crocheting, following grandchildren as they participate in sports.

Honors/Awards: John Becker Research Award, 2015; College of Business and Technology Scholarship Award, 2011-12; Phil Fisher Service Award for Society for Case Research, 2013 and 2015; MBAA International McGraw-Hill/Irwin Distinguished Paper Award, 2013.

Areas of research/specialization: Case research and research on pedagogy.

Courses taught: Principles of Management and Business Ethics. Previously taught Business Communications and accounting.

Recent Published Articles:

- “Send Him With Todd,” Journal Of Case Studies, 2016.

- “Talk To Me!! Effective, Efficient Communication,” The Journal of Research In Business Education, 2015.

- “Business Fundamentals for Health Care Providers: Ensuring Effective Practice Management and Good Stewardship,” Journal of Health Administration Education, 2015.

- “The Society for Case Research: An Organization Built on a Culture Of Success,” Business Case Journal, 2015.