Researcher Dr. Susanne George Bloomfield has a story to tell. To be more precise, three stories. Dr. Bloomfield is not only Distinguished Martin Professor of English at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, but an outstanding historical biographer, penning three books about women writers who lived in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“I like to set the women and their writings in the context of the social, political, and economic culture of the region,” Dr. Bloomfield remarked. Focusing on once prominent women at the turn of the century, she has analyzed and written biographies of Elinore Pruitt Stewart, Kate Cleary, and Elia Peattie, all stories that exemplify the struggles and successes of women during the settlement period of the frontier.

Rural and Urban Pioneers

Dr. Bloomfield’s biographies show the rich—if sometimes difficult lives—that these women lived. Elinore Pruitt, born at Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1876, spent her childhood in the Indian Territory, teaching herself to read and write with the help of the owner of a local general store. When Elinore was eighteen, both her parents died, and she assumed the task of raising five of her eight younger siblings, working as a laundress for the rail-road. A marriage ended, presumably in divorce although she told everyone she was a widow, and she took her daughter Jerrine to Denver where she worked as a housekeeper for an elderly lady.

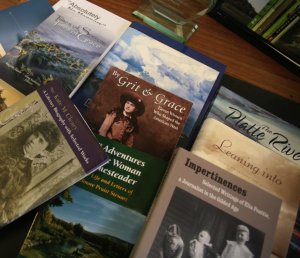

Determined to better her life by homesteading, in 1909 Elinore answered an ad for a housekeeper placed by Clyde Stewart at his isolated ranch in Burnt Fork, Wyoming. Six weeks later she married the 41-year-old widower. Elinore wrote regular letters to Mrs. Coney, her former employer, who was impressed with the stories and arranged for them to be serialized in The Atlantic Monthly. They later appeared in two books, Letters of a Woman Homesteader (1914) illustrated by N.C. Wyeth and Letters on an Elk Hunt (1915). Her books are still in print, and the 1983 movie Heartland, which won national and international awards, was based on her life.

Dr. Bloomfield’s research on Stewart led her to the discovery of other women writers who were also pioneers, each in her own way. Kate Cleary and Elia Peattie, both from Chicago, moved to Nebraska in the 1880s, and each stayed about 10 years. “These two women are significant in the exploration of the lives of what I term ‘urban pioneers,’ those women not living in sod houses on the desolate plains but still involved in the birth and growth of villages and cities during the settlement period of the West,” Bloomfield said.

Dr. Bloomfield’s research on Stewart led her to the discovery of other women writers who were also pioneers, each in her own way. Kate Cleary and Elia Peattie, both from Chicago, moved to Nebraska in the 1880s, and each stayed about 10 years. “These two women are significant in the exploration of the lives of what I term ‘urban pioneers,’ those women not living in sod houses on the desolate plains but still involved in the birth and growth of villages and cities during the settlement period of the West,” Bloomfield said.

Kate Cleary and her husband, a lumberman, helped build the village of Hubbell, Nebraska. Kate, called one of the region’s leading humorists by the Chicago Chronicle, published sketches, stories, and poems realistically capturing everyday life in the fledgling community. Many of her writings are amusing, light-heartedly satirizing social conventions and the foibles of human nature; others, however, depict the heartbreakingly harsh life of her neighbors.

From East to the Struggling West

Kate’s married life began like many other Victorian women trans-planted from eastern cities to the isolated towns on the plains, devoting her life to her children and husband. However, she lost two of her six children and almost died herself. While battling childbirth fever, her country doctor addicted her to morphine, a typical treatment of the time. She spent her life fighting to overcome it during an era when ineffective cures were basically to be survived. Throughout it all, she continued to care for her family and kept writing.

Ironically, Dr. Bloomfield’s research uncovered the fact that Elia Peattie, her next subject, had been a close friend of Kate Cleary. Elia, who was the first woman reporter for the Chicago Tribune, moved to Omaha with her husband. There she and her husband were both employed by the World-Herald where Elia became the first woman to have a regular column and bylined editorials. Elia, however, was no common journalist; her legacy exists in her literary as well as in her personal and political contributions to society.

Peattie’s writings depict not only the transformation of Omaha in the 1890s toward the progressive, just society that she envisioned but also reflect the passion of a woman convinced of each individual’s ability to effect positive, lasting change within society. In artistically crafted prose, she challenged her readers to look within themselves to question their beliefs and then act upon them with passion and commitment. She expected nothing less of her self or of her readers; she expected everyone to rise to the level of uncommonness.

Dr. Bloomfield began her research for each biography by traveling across the United States from Philadelphia to Selah, Washington, and from Chicago to Burnt Fork, Wyoming, to interview surviving family members, who shared private docu-ments with her, and to visit the places these women called home. She continued collecting material by visiting the archives of various state and county historical societies in Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming, California, Missouri, and Illinois and speaking with local historians. “Most of my research involved primary materials,” she said, “including miles and miles of microfilm of historic newspapers.”

“My writing has enriched my teaching of writing in the areas of literary criticism and creative nonfiction,” Dr. Bloomfield said. “In my classrooms, my students learn the process of gather-ing materials from both primary and secondary sources, interpreting this information and organizing it into a coherent and unified text just as I research and compile a book.”

Freshman composition students regularly compose their own mini-books, either choosing a subject to interview and research or compiling a story of their own lives. “I encourage primary research and interpretation at all levels, from freshman to graduate students,” she added. “They learn that completing a project is not a linear process, for they must decide what to take out, what to leave in, and how to arrange it coherently and creatively.”

Giving Voice to Silences

Silences by Tillie Olson initiated Dr. Bloomfield’s interest in reclaiming women’s lives. “Reacquainting today’s readers with writers from the past who were once well-known and well-respected but have been forgotten during the last 100 years has become a quest for me,” Dr. Bloomfield remarked. “Not only are these nineteenth century women’s works memorable and important as literary and historical documents, but their lives are inspiring, too, and they can serve as models for us in contemporary society.”

“Biographies are an excellent way to enlarge the ever-growing understanding of Western history at the turn of the nineteenth century, not only of the pioneer experience but also of women’s literary history,” Bloomfield said.

When the stories of these women are told, it gives new perspect-ives on contemporary America. As the old saying goes, you can’t know where you are going unless you know where you have been, and Dr. Bloomfield is working diligently to solve that problem.