VIEW THE 2021 NEW FRONTIERS RESEARCH MAGAZINE

By TYLER ELLYSON

UNK Communications

Most Nebraskans have never heard of Celia and Eliza Grayson.

Unlike the man who owned them, Stephen F. Nuckolls, their names largely faded into history.

“A lot of people don’t realize there were enslaved people in Nebraska,” said Gail Shaffer Blankenau, a professional genealogist and researcher from Lincoln.

She’s hoping to change that.

In her master’s thesis – “Journey to Freedom from Nebraska Territory” – Blankenau shines a light on this dark part of early Nebraska history by addressing slavery through the eyes of Celia and Eliza, two young Black women who became “unlikely leaders” in the abolitionist movement when they fled the Nuckolls household in 1858.

“These two women did more than escape their particular circumstances. Celia and Eliza’s choice to pursue their freedom was a challenge not only to their ‘master,’ but also to the territorial system established by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act under the theory of popular sovereignty,” Blankenau writes.

THE PROBLEM WITH POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY

Stephen Nuckolls is best known as the founder of Nebraska City, where Nuckolls Square Park still bears his name. He’s also the namesake of Nuckolls County (located along the Kansas border about 140 miles to the west) and a former member of the Nebraska Territorial Legislature.

The native Virginian was one of the early settlers of Nebraska Territory, and one of its first slave owners. When he arrived in 1854, the nation’s slavery debate was far from settled.

“If it hadn’t been for the slavery question, I don’t think it would have been that controversial to open up the Nebraska and Kansas territories,” said Blankenau, who graduated in July 2020 with a Master of Arts in history from the University of Nebraska at Kearney’s online program.

“The reason it was controversial was the prospect of expanding enslavement into western territories. As many people know, the 1850s, right before the Civil War, was a period of considerable upheaval over the question.”

The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created the two territories, used the popular sovereignty principle to address this issue, allowing the settlers of a territory to decide whether slavery would be allowed there. Drafted by U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, this legislation overturned the Missouri Compromise’s use of latitude as the boundary between slave and free territories.

Most people assumed that if slavery took hold, it would be in Kansas rather than Nebraska, but the act left the door open for slavery to enter both territories.

“One of the ambiguities of the popular sovereignty theory within the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the question, ‘Are people free until the territory votes for enslavement or are they enslaved until the territory votes to prohibit it?’ And that really wasn’t clear,” Blankenau said. “We’d talked about free states, but no court had ever said what happens in a territory where they hadn’t voted one way or the other.”

In Kansas Territory, conflicts between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers led to a period of violence known as “Bleeding Kansas” and helped pave the way for the Civil War.

Although violence never reached that level in Nebraska Territory, Blankenau argues that popular sovereignty didn’t work particularly well there either. The Territorial Legislature made several unsuccessful attempts to prohibit slavery prior to 1861, but that legislation was either tabled by the Territorial Council or vetoed by the federally appointed governor.

“The question of whether slavery was legal or not during that early territorial period was never completely settled,” Blankenau said.

SLAVERY IN NEBRASKA TERRITORY

Celia and Eliza Grayson were born in Grayson County, Virginia, where they either adopted or were given their last name. The children, who Blankenau believes were sisters, were enslaved by the Nuckolls family.

In 1846, when Celia was 11 and Eliza was 9, the Nuckolls family and their “property” relocated to Atchison County in northwest Missouri. Eight years later, Stephen Nuckolls brought four slaves with him, including Celia and Eliza, when he crossed the Missouri River to settle in the newly opened Nebraska Territory.

“They were on the ground as early as anybody, Black or white, in Nebraska territorial history,” Blankenau said.

The former site of Fort Kearny, Nebraska City flourished as a transportation hub because of its location along the Missouri River and was a contender for the territorial capital.

It’s also where most of the territory’s enslaved people lived.

Censuses never showed more than 11 slaves in Nebraska Territory, according to Blankenau, but she believes the number was much higher.

“It was definitely an undercount,” she said, noting that slaves at military forts often weren’t counted. She also suspects many people living in or near Nebraska City kept slaves in Missouri to avoid controversy and property taxes.

“There was a lot more going on than I think prior historians have found in that southeast corner of Nebraska,” Blankenau said.

Celia and Eliza were in Nebraska Territory for four years before they made their break for freedom.

A DARING ACT

It was a cold night in late November 1858 when the two women, ages 22 and 20, slipped away from the Nuckolls household.

John Williamson, a Black and Native American man from Iowa, guided them through the darkness to a Missouri River crossing about 6 miles north of Nebraska City. They boarded a skiff, crossed the icy waters and made their first stop on the Underground Railroad at Civil Bend, Iowa.

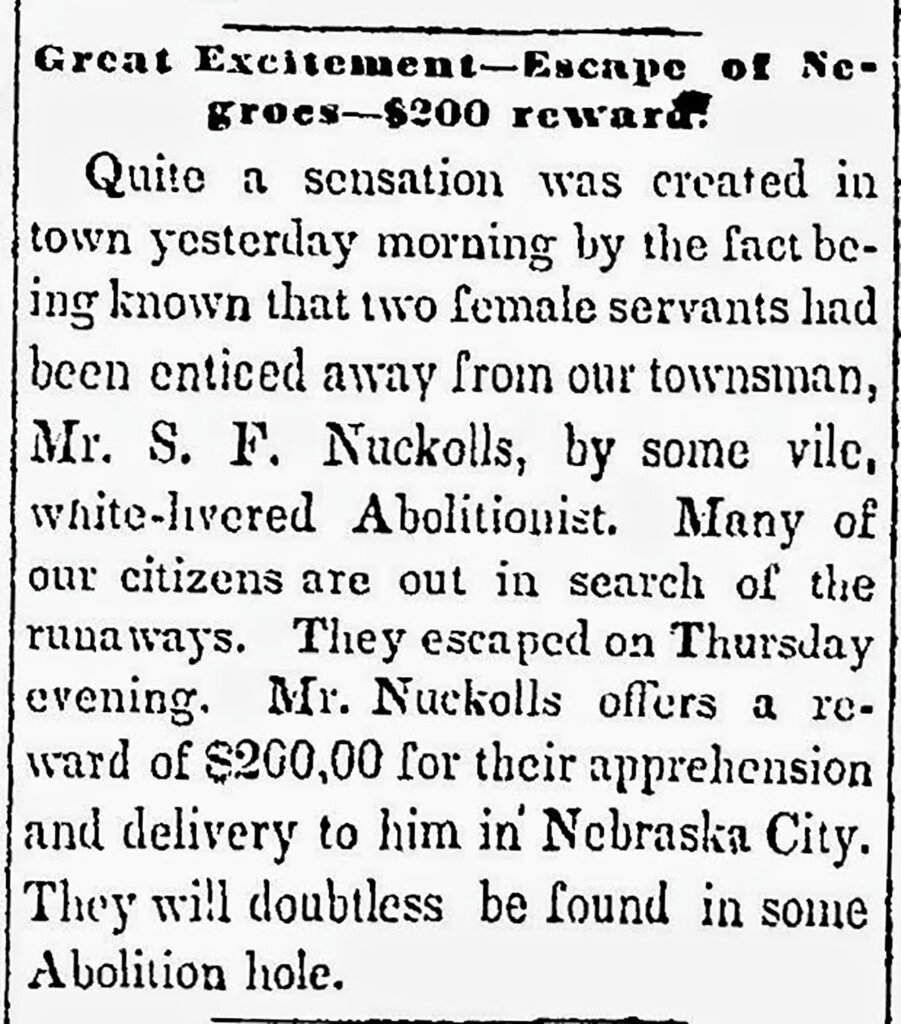

The following day’s edition of the Nebraska City News declared that Nuckolls’ “female servants” had been “enticed away” by “some vile, white-livered Abolitionist” and would “doubtless be found in some Abolition hole.” He offered a $200 reward for their return.

The following day’s edition of the Nebraska City News declared that Nuckolls’ “female servants” had been “enticed away” by “some vile, white-livered Abolitionist” and would “doubtless be found in some Abolition hole.” He offered a $200 reward for their return.

“When they left, they challenged the entire system,” said Blankenau, noting that the escape made national news because it highlighted the issues with popular sovereignty and the spread of slavery into western territories.

Nuckolls, however, wasn’t going to let Celia and Eliza go without a fight. He brought a posse to Civil Bend to search for them.

“They tore that place apart looking for Celia and Eliza, but they never found them,” Blankenau said. “Only later did some of the abolitionists who helped them talk about what happened.”

It’s unclear what became of Celia, but Eliza ended up working as a servant in a Chicago brothel. She was betrayed after sharing her story with a woman there and, in November 1860, Nuckolls went to Chicago to capture Eliza, who he valued at $1,200.

The federal Fugitive Slave Act supported Nuckolls’ effort, requiring law enforcement to assist him, but that’s not what happened. Nuckolls and Eliza were both arrested for disorderly conduct, and Eliza was taken to an armory building. When sheriff’s deputies attempted to transfer her to a nearby jail, a group of abolitionists whisked her away to safety.

Little is known about Celia and Eliza’s lives after 1860 – Blankenau believes both women “almost certainly” fled to Canada – and there are no monuments recognizing their daring escape.

Nuckolls, meanwhile, filed lawsuits in Nebraska Territory and Chicago against the people who helped them find freedom.

“It was expected that both suits would make it to the Supreme Court to finally settle whether they were free or whether they were enslaved,” Blankenau said.

That became a moot point in 1861, when the Nebraska Territorial Legislature voted to override the governor’s veto and prohibit slavery. The Civil War, which ultimately decided the fate of slavery in America, also began that year.

Nuckolls, whose family back in Virginia fought for the Confederacy, went on to serve as a U.S. Congress delegate for Wyoming Territory and as a delegate to the Democratic National Conventions in 1872 and 1876.

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

Blankenau received UNK’s Outstanding Thesis Award for her research project.

The recognition was an honor, but Celia and Eliza were her inspiration.

“I just became more and more amazed by these two women and their courage,” she said. “This turned out to be an absolutely fascinating project and it continues to fascinate me. It touches on so many important issues from that time period that all kind of came to a head in Nebraska.”

A charter member of the Great Plains chapter of the Association of Professional Genealogists and owner of Discover Family History, a genealogy and research business based in her Lincoln home, Blankenau leaned on her professional skills to tell the story.

“Reconstructing a history of enslaved people from this time period was difficult,” she said. “We don’t have any records from their point of view.”

She found plenty of other primary sources, though.

Blankenau scoured the Nuckolls family papers at the History Nebraska archives in Lincoln, located online census data and land records, studied newspaper accounts, accessed records from county courthouses in Nebraska, Iowa and Missouri, contacted historical societies and drove to Des Moines to view the State Archives of Iowa. She also received family letters from a relative of Nuckolls’ wife Lucinda.

Following a recommendation from her thesis committee, Blankenau plans to turn the 291-page document into a manuscript for publication. But first, she wants to do a little more digging.

Blankenau found a Civil War pension record for a man named Shack Grayson who served in the United States Colored Troops and fought for the Union Army. He is likely the same Shack Grayson who lived in the Nuckolls household in Nebraska City with Celia and Eliza.

She also believes Celia and Eliza had another sister, Edith, who was enslaved by the Nuckolls family in Missouri before moving to Nebraska City after the war.

“There’s more to the story,” Blankenau said, and she wants to finish telling it.