By TYLER ELLYSON

UNK Communications

KEARNEY – Keith Geluso slowly climbed the ladder, wearing a Black and Decker work glove on one hand and holding a pair of metal forceps in the other.

“Hopefully they’re up here,” he said before peering into a crack between the exterior wall and roof of an old sod-and-frame building at Fort Kearny State Historical Park.

“Oh yeah.”

Geluso had spotted exactly what he was looking for. About a half dozen bats were nestled in the small opening, just as he expected.

The University of Nebraska at Kearney biology professor carefully removed one of the screeching animals, then displayed it in his hands.

“That’s a good-looking bat,” he said.

This up-close encounter might seem frightening to some, but not Geluso, who earned his “Batman” nickname by dedicating his career to researching the world’s only flying mammal and dispelling myths about a creature he considers “quite cute.”

“I’ve always been fascinated by people’s excitement and fear, at the same time, about bats,” Geluso said.

He can thank his father Ken for that.

A longtime bat biologist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Ken introduced his son to the profession, and a lifelong passion, when he was about 5 years old.

“My mom says I was brainwashed at an early age,” the younger Geluso said.

He went on research trips with his father and tagged along when Ken was asked to give presentations for schools or nonprofit organizations.

Now, Geluso is the bat expert people turn to and his father, who retired about 10 years ago and moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, serves as his field assistant.

A LOT TO LEARN

Bats represent about 20% of all mammal species on Earth, but they’re small, nocturnal and difficult to study.

“There’s still a lot to be learned about these animals, and they’re in our backyards and houses,” Geluso said.

That’s part of the appeal for the UNK field biologist.

He’s studied bats across the United States, Central America and Caribbean in an effort to uncover information about their diets, habitat, reproductive cycles and migration habits.

Geluso mainly splits his time between his native Nebraska, where 13 bat species can be found, and New Mexico, where there are about 30 species.

“New Mexico has a lot of elevational difference, a lot of different habitats, so there is more diversity of bats down there,” said Geluso, who received his bachelor’s and doctorate degrees from the University of New Mexico and met his wife Mary Harner, an associate professor in UNK’s Department of Communication, at the school. He holds a master’s degree from the University of Nevada.

In New Mexico, where he often travels with students, Geluso is currently studying three rare species of nectar-feeding bats he plans to write about next spring. He’s also working on a project involving two species of migrating red bats that are adversely impacted by wind farm development.

“Very basic information is lacking for most of these bat species, such as which states they appear in,” said Geluso, who was able to determine through molecular data that biologists can use an external color difference to identify these two red bat species.

He’s planning a bat survey in Gila National Forest for summer 2020, and he also takes a group of high school students to Arizona and New Mexico each summer to study bats and other animals through a biology camp organized by the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas.

In Nebraska, Geluso and his students have studied bat migration patterns for more than 10 years in the Panhandle to better understand the dangers they may face from wind turbine construction and another research project in Pine Ridge National Recreation Area focused on forest management techniques that help protect the state’s most diverse bat population.

They also study bats in the Happy Jack Chalk Mine near Scotia and were the first to survey bats along the Republican River in 2008, when a UNK student documented a bat that wasn’t expected to be in the area.

“There were almost no bat records in southwest Nebraska when I got here in the late 2000s,” said Geluso, who joined the UNK faculty in 2006.

Of concern for Geluso and other biologists is the spread of white-nose syndrome in eastern Nebraska, where the fungal disease has decimated certain bat populations.

“It’s kind of a scary time for bat biologists right now,” he said. “I don’t know if I’ll ever go back to eastern Nebraska to try to catch bats. The population of a few species has crashed.”

White-nose syndrome has killed millions of bats in North America.

“New bats have been listed as federally threatened because of that fungus,” Geluso said.

This should be alarming for Nebraskans, according to Geluso, because bats are the top consumers of night-flying insects such as mosquitoes and they also eat beetles, moths and other insects that damage crops.

“It’s staggering what ecological services just the insect-eating bats do here in the United States,” he said. “They’re huge for controlling the insect populations.”

POPULAR PRESENTER

In addition to his research, Geluso, who also studies rats, birds, reptiles and amphibians, carries the torch for his father as a sought-after presenter.

Of course, he’s in high demand this time of year, when Halloween increases interest in bats and other creepy creatures.

Geluso was the first person Horizon Middle School teacher Staci Cahis thought of when she was lining up guest speakers for her exploratory wildlife biology class.

“I want students to be exposed to as much wildlife as possible, and he’s the expert on bats. Plus, he knows where to catch them,” she said with a laugh.

Cahis, a UNK graduate who’s currently working on a master’s degree, asked Geluso to visit her classroom for a second time this semester, after the first group of students picked his presentation as their favorite.

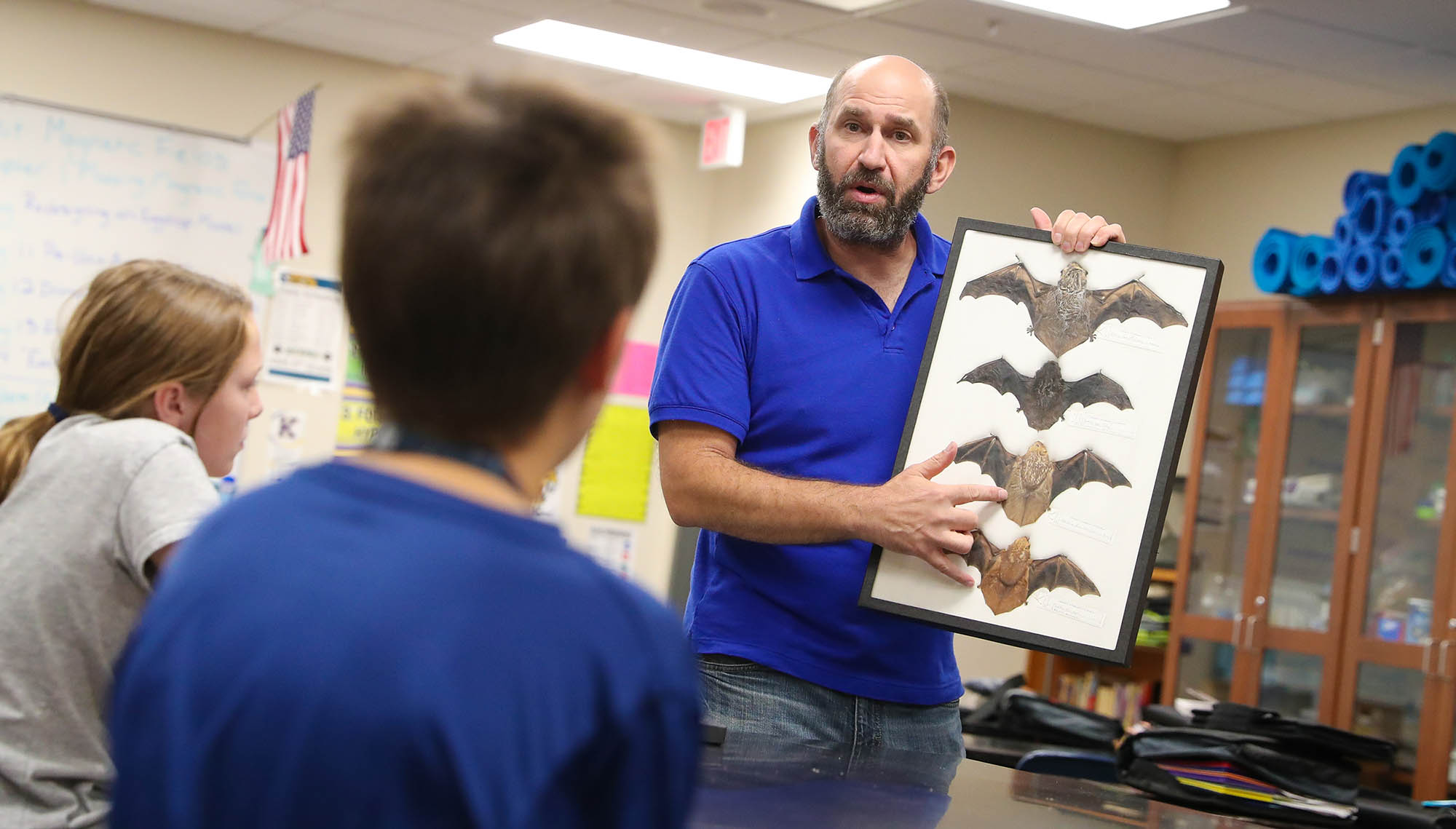

His popularity can be credited to the live bat Geluso brings to each presentation.

“If I have a live bat when I walk into a classroom, I don’t need to prepare anything,” he said. “That’s what they really want to see.”

Some of the roughly 20 students in Cahis’ classroom were a bit apprehensive – “It looks like a gargoyle,” one noted – but most were excited to touch its soft fur and thin wings.

“How often do you get to see a bat up-close?” Cahis said. “It’s something unique they’re not exposed to every day.”

Geluso uses the presentations to educate students about bats, promote the animal’s benefits and, hopefully, ease any fears.

“People get nervous around bats,” said Geluso, who has presented in schools throughout central and western Nebraska, as well as Ash Hollow State Historical Park and Indian Cave State Park.

And it’s not just children who are uneasy.

Geluso also responds to calls from Kearney residents who find a bat in their home, something that happens “fairly frequently” during the fall when the critters are looking for places to hibernate.

“Bats are common in buildings in Kearney,” said Geluso, who estimates 1 in 3 houses has them.

The UNK professor helps residents capture and safely release the bats – he returns the animals used in presentations to the wild, as well – and shares tips on how to keep them out of homes.

He also offers a few bat facts to calm the nerves.

“Rabies is very rare and uncommon in bats,” said Geluso, noting that humans can’t be infected unless they’re bitten by a bat carrying the disease. That usually doesn’t happen unless they’re trying to pick up an injured or sick animal.

And you can forget all that Halloween and horror movie hoopla about bats attacking people.

“I can stand in Carlsbad Caverns National Park and have 300,000 to 400,000 bats come out and they just fly right around me,” Geluso said.

Then again, he is “Batman.”