By TYLER ELLYSON

UNK Communications

KEARNEY – One year ago, thousands of people flocked to Nebraska to witness “The Great American Eclipse.”

The solar eclipse, spanning from Oregon to South Carolina and casting a 70-mile-wide shadow along the path of totality, was a once-in-a-lifetime spectacle for many observers staring at the sky through those special cardboard glasses.

Watching the sun disappear midday was an awe-inspiring moment for spectators, but two researchers at the University of Nebraska at Kearney were equally interested in some less-obvious reactions to the big event.

Mary Harner, an associate professor in the departments of communication and biology, and Emma Brinley Buckley, a research scientist in the department of communication, conducted a study investigating the biological and environmental effects of the Aug. 21, 2017, solar eclipse.

The resulting article – “Assessing Biological and Environmental Effects of a Total Solar Eclipse with Passive Multimodal Technologies” – details observations from that day as recorded by a network of time-lapse and trail cameras, sound recorders and environmental sensors installed at sites along the Platte River to determine how this ecosystem responded to the rare occurrence.

Their findings, published earlier this month in the journal Ecological Indicators, reveal a combination of expected and surprising outcomes.

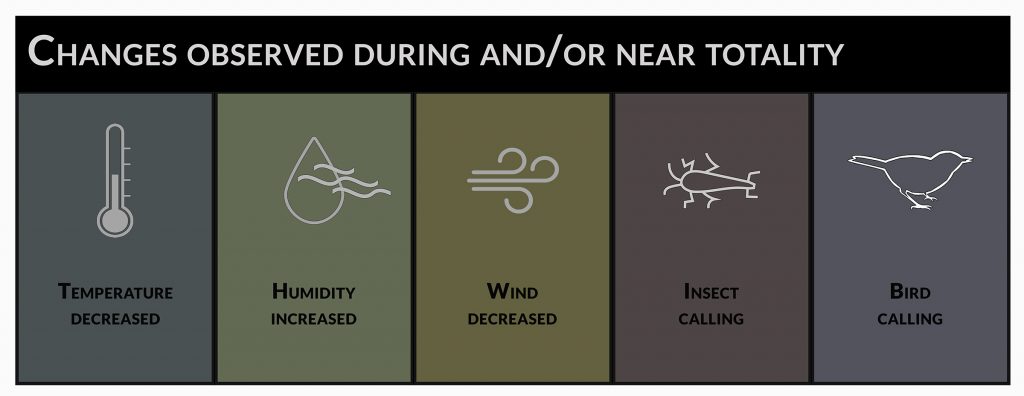

Shortly after totality, when the moon completely blocked the sun, temperatures decreased an average of 12 degrees and humidity increased about 20 percent. That was expected; however, an interesting comparison showed a wooded area they monitored experienced less of a temperature shift than a prairie site located just 20 miles away.

Sound recordings also indicated a reduction in wind near totality, a phenomenon known as “eclipse wind.”

“It was pretty neat to be able to pick that up on the sound recordings,” said Brinley Buckley, who had never heard the term prior to this project.

Although many of the recorders were in relatively isolated locations, Harner noted that they still picked up the sounds of people cheering and yelling during the eclipse’s climax.

A total solar eclipse doesn’t engulf the landscape in complete darkness. The researchers looked at time-lapse photos taken every 30 seconds to determine the level of illumination declined an average of 67 percent at totality, similar to dawn or dusk. Still, this was enough to change the habits of some birds and insects.

The researchers discovered the calling activity of birds was impacted by the eclipse. Sedge wrens, for example, increased their singing near totality, and western meadowlarks had the opposite reaction.

The sound recordings also captured a shift in insect calls from diurnal to nocturnal species, such as katydids and crickets, as the sky darkened, and the frequency of these calls got lower as the temperature dropped.

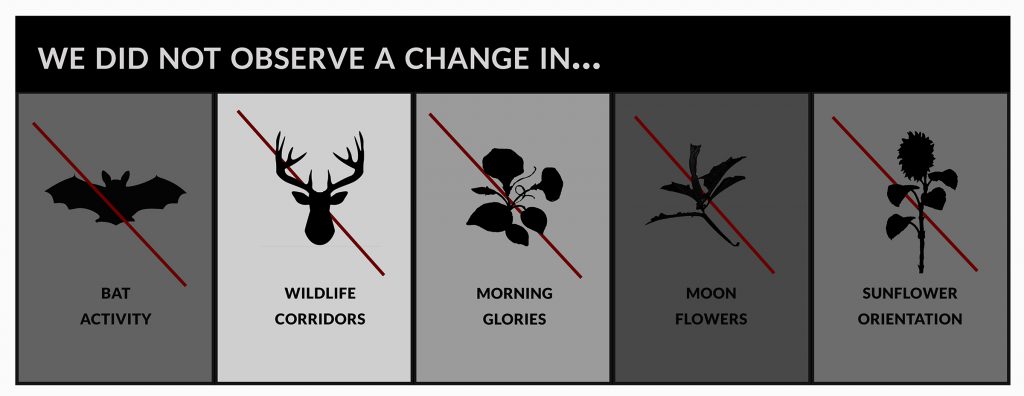

The researchers hypothesized that plants and other animals that respond to changes in light may alter their behaviors – such as flowers closing their petals, bat colonies coming to life and unusual wildlife movement – but trail cameras and ultrasonic microphones didn’t pick up any of this activity.

“It was a little bit surprising that we didn’t detect changes from the trail cameras that we had on the landscape,” Harner said.

In addition to documenting a rare event, Harner said the project is an example of how collaboration among diverse disciplines can advance research and education.

This research, supported in part by the University of Nebraska Collaboration Initiative, was a partnership between UNK, the Crane Trust, Center for Global Soundscapes at Purdue University and Platte Basin Timelapse project, which is based at the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“Our teams had been working together in various capacities, but this was a way to come together and really formalize some of the things we had been laying the foundation for,” Harner said.

The Center for Global Soundscapes added sound recorders at grassland sites near the Rowe Sanctuary and Crane Trust a couple years ago, and Harner and Brinley Buckley are both part of the Platte Basin Timelapse project, which started in 2011.

That project, co-founded by Michael Forsberg and Michael Farrell, assistant professors of practice in agricultural leadership, education and communication at UNL, uses a network of more than 60 time-lapse cameras placed throughout the 90,000-square-mile Platte River basin to create multimedia resources and share stories about the river and other water sources.

Brinley Buckley joined the Platte Basin Timelapse project while earning a master’s degree in natural resource sciences from UNL and Harner, a biologist with a focus on river and flood plain ecosystems, works with the team as an ecologist.

Harner said these partnerships are an “incredible opportunity” to support experiential learning for UNK students as they get involved with future projects.

“We definitely see that continuing to be a focus and a long-term collaboration,” she said.

The UNK researchers believe the network of cameras, recorders and environmental sensors can be used to study larger-scale ecological changes over a longer time frame, with the sights and sounds adding to the science and their ability to capture an audience’s attention.

“That network is very powerful well beyond the beautiful pictures that come from the cameras,” Harner said.

Video Courtesy of Mariah Lundgren, Platte Basin Timelapse