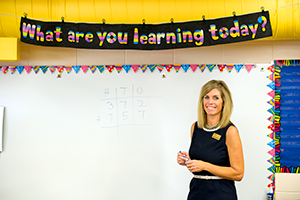

Jane Strawhecker

Professor and Assistant Chair for the Department of Teacher Education

Leave it to math education specialist Jane Strawhecker to apply the multiplier effect to her career as a way to influence the quality of education for more students than was possible as an elementary and middle school teacher.

Leave it to math education specialist Jane Strawhecker to apply the multiplier effect to her career as a way to influence the quality of education for more students than was possible as an elementary and middle school teacher.

Strawhecker, a professor and the assistant chair in the Department of Teacher Education, is an award-winning teacher whose research is focused on finding ways for the next generation of teachers to be even more effective. As an elementary and middle school teacher, she taught math concepts. Today, she teaches, and continues to research, the best methods to teach those concepts.

“I had 14 years of teaching experience, and I loved teaching, so it was a pretty seamless transition to go from teaching elementary school children to teaching future teachers what I knew,” Strawhecker said.

Her office in the College of Education Building reflects her passion for teaching. Before you enter, a sign alongside her door says: “Do math, and you can do anything.”

Once inside, a plaque on one wall reads: “A teacher makes you feel good about who you are and inspires you to become all you can be.” Just above her desk on another wall hangs a framed copy of the “Oath for Mathematics Teachers,” and above the oath hangs a whimsical black and white clock. The round face of the clock, which looks like an old-fashioned chalkboard, has math problems–addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, square roots and algebra—to solve for each of the 12 time numbers. Noon or midnight is measured by 6×2. The square root of 4 is the answer for 2 o’clock, and there’s even a “pi” part of the equation for 9 o’clock.

Of all the various kinds of math problems to work with, Strawhecker has been especially interested in finding better ways to teach fractions—an interest that has led her to develop a novel way to teach the concept.

Of all the various kinds of math problems to work with, Strawhecker has been especially interested in finding better ways to teach fractions—an interest that has led her to develop a novel way to teach the concept.

She has developed what she calls a “fraction slide,” a math manipulative designed to help upper elementary students more clearly understand the connections between fractions. The fraction slide is a rectangular box with two strips of numbers and an attached device that highlights fractions for comparison. With the symbolic representation of “friendly” fractions, the handheld slide includes halves through twelfths.

For example, she said, a student could be asked if he wants . of something or 4/7ths. The fraction slide lets a student look for a common denominator, in this case 14, to see that it is a comparison of seven parts of 14 to eight parts.

“My idea for the fraction slide developed gradually, having first thought about this sort of tool in the mid-1990s,” she said. “In the beginning, I used Popsicle sticks and created sets for my students who needed to use them as a transition from fraction manipulative work to algorithmic (step-by-step) work.

“A few years ago, I put the Popsicle sticks aside, and enlarged and cut apart a multiplication table, which was a much more efficient way to develop sets of fraction strips for use with students. And that is the way I began showing students how they could manipulate four strips to show fractions with like denominators.

“Once the denominators are alike, students can compare fractions, add fractions or subtract fractions. I still had to physically use my fingers to isolate the new fractions with like denominators. That’s when the idea of a ‘slide’ came into play.

“Ideally, a student would have access to two of these, so he could compare fractions or compute with fractions.” Currently, she is looking at ways to further refine the prototype she has had built.

“Ideally, a student would have access to two of these, so he could compare fractions or compute with fractions.” Currently, she is looking at ways to further refine the prototype she has had built.

The idea for a fraction slide is an outgrowth of her teaching experiences. She was an elementary teacher with the Omaha Public Schools from 1986-1988 and then a middle school math teacher in the Blue Valley School District in Overland Park, Kan., for seven years, before moving to Kearney to teach elementary grades in the Kearney Public Schools from 1995-2000.

She earned a bachelor of arts degree in elementary education, with an elementary mathematics minor, from Kearney State College/UNK in 1986. She received a middle school endorsement a year later, and then went on for a master’s degree in education from MidAmerica Nazarene University in Olathe, Kan., in 1992. In 2004, she earned a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction, with an emphasis on K-8 mathematics education, from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

One teaching challenge she faced, especially with middle school students, was to change the minds of children who came to her classes with the idea that math was too hard and/or didn’t apply to them.

“When math makes sense to you, you’re not afraid of it,” she said. “So I would try to get them to see that math is broad, and there was something in math they could be good in.

“What I liked about middle school,” she said, “was I could teach math most of the day, but I liked the ages and attitudes of fourth and fifth graders, too.”

Her reward often has been in helping children learn to use numbers to understand how things work.

“It’s all pretty rewarding,” Strawhecker said with a broad smile, noting that she applies that thinking to her own life—using math to help her see the angles in winning shots on the tennis court.

In the Department of Professional Teacher Education, she serves as an adviser for curriculum and instruction for math master’s degree candidates, teaches graduate and undergraduate math education classes, and supervises math field experiences for UNK students at up to six schools per semester. Each year, she has 80 to 100 teachers-in-training in her UNK classrooms.

Her classroom experiences, past and present, drive her research. One example is her most recent study of the outcomes of co-teaching math content and math pedagogy for elementary preservice teachers.

Traditionally, teacher education majors for elementary, special education and early childhood education focus on education classes first and then add in the content areas, because they will teach all subjects.

In contrast, secondary students major in a content specialty and then add the education methods classes. Middle school education majors currently are in the first group, Strawhecker said, but will follow the secondary educators’ path beginning this year.

In both cases, content and methods (ways to present content) have been taught separately. However, a year ago, she and Pari Ford, an assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics, teamed up to co-teach math content and math pedagogy for elementary pre-service teachers concurrently as a pilot study.

The research into combining the two aspects of teacher preparation was recently published in Issues in the Undergraduate Mathematics Preparation of School Teachers: The Journal. Based on the positive outcomes of teaching content and pedagogy together, the two have sought grant funding to support further refinements to their pilot study.

Strawhecker has also secured grants to enhance teacher effectiveness. An Eisenhower Professional Development Grant for Mathematics supported a “Preparing Tomorrow’s Elementary Teachers” project, and an American Association of State Colleges & Universities grant focused on “Improving the Mathematics Subject-Matter Preparation of Elementary School Teachers.”

UNK teacher education students in Strawhecker’s classes are required to do 25 hours of supervised field experience at area schools. Four students commonly are assigned to the same classroom. Although two may be preparing lesson plans, two are in the classroom at any one time.

“This is a pre-student teaching experience,” she said, which helps students prepare, teach and analyze their students’ work. “Perfection isn’t the goal. It’s getting comfortable with the content and the delivery of the content.”

The field experience for teacher education students was the focus of a study “Preparing Elementary Teachers to Teach Mathematics: How Field Experiences Impact Pedagogical Content Knowledge.” The study was published in Issues in the Undergraduate Mathematics Preparation of School Teachers: The Journal. So what works in the classroom?

“Finding ways to engage students,” Strawhecker said, which can include cooperative learning tasks, having students explain their thinking and how they approached a problem, and making connections between and among concepts.

She said that as an elementary teacher, she would tie math and real-world lessons together, such as showing a video of Olympic competitions and talking about how math is a part of the events. Classroom teachers also use a variety of technology tools, such as smart boards and tablets, which can be used to engage students in visually appealing ways.

“They (technology tools) do have a place in the classroom when they’re used at an appropriate time for practice or to aid the teacher in showing why a concept works in a certain way,” Strawhecker said. “There are pretty high expectations for young learners, things I don’t remember learning until I was older Technology can also play a role in student teachers presenting their work in the classroom and in presenting themselves as candidates for teaching positions. Strawhecker has published her joint research into the use of electronic portfolios in both of those settings. “The Use of Electronic Portfolios in an Elementary Mathematics Methods Class” was published in the Eastern Education Journal, and “The Role of Electronic Portfolios in the Hiring of K-12 Teachers” was published in the Journal of Computing in Teacher Education.

When she isn’t publishing her own work, she is reviewing the work of others. She has reviewed eight different mathematics textbooks in the past six years. And she is in demand as a presenter. She has given nearly 30 presentations at conferences, faculty development sessions and other meetings of educators. Those presentations have taken her to Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Nevada, South Carolina and Washington, D.C., as well as across the state of Nebraska.

Her own skills in the classroom earned her campus-wide recognition in 2007 when she was awarded the prestigious Pratt-Heins Award for Teaching. A year earlier, she had received the UNK College of Education Outstanding Teaching Award and the UNK Mortar Board Teacher Recognition.

The Pratt-Heins Award for Teaching is “…based on evidence of consistent outstanding teaching as evidenced by peer evaluations from departmental faculty, the department chair and dean of the nominee’s college.”

In presenting the award, Pratt-Heins Foundation Trustee Tom Tye II described Strawhecker as “…truly an outstanding educator who makes a difference, in real ways, with teaching candidates, practicing teachers and also with elementary-aged youngsters.”

Further, her nominator wrote: “The foundation for our renewed undergraduate teaching programs is commitment to a field-based delivery model. I believe her most significant teaching accomplishment is an unusually high aptitude for teaching in this cutting edge, dynamic, fluid and complex environment.” When asked about the skills that make a good teacher, Strawhecker said, “A strong work ethic and with that work ethic, being able to prioritize.”

“Being a lifelong learner, you are always looking for meaningful tasks you can take into the classroom,” she said. “There is no one right way to teach.”

Strawhecker said her goal is to teach her students to be effective teachers. Although, as a teacher of teachers, she knows she doesn’t always get a good measure of her success. She also knows that the results of her work today won’t be fully known for years, when her former teacher education students are successful in their own classrooms and may make links between what they are doing and what they learned at UNK.