By KIM HACHIYA

It’s hard to imagine a better ambassador for the University of Nebraska at Kearney than Chuck Rowling. As he strides across campus, his eyes gleam with pride as he points out various landmarks.

And he offers this: “I really, almost literally, grew up on this campus. I went to the college’s preschool. My brothers and I would swim in the campus pool. We spent so much time in my dad’s office. This place really shaped who I am.”

Rowling is an assistant professor of political science who joined the UNK faculty in 2012, less than 10 years after earning his bachelor’s degree from UNK. His route back to Founders Hall seems both pre-ordained and random. But his passion for students, for teaching and for research makes that path seem obvious.

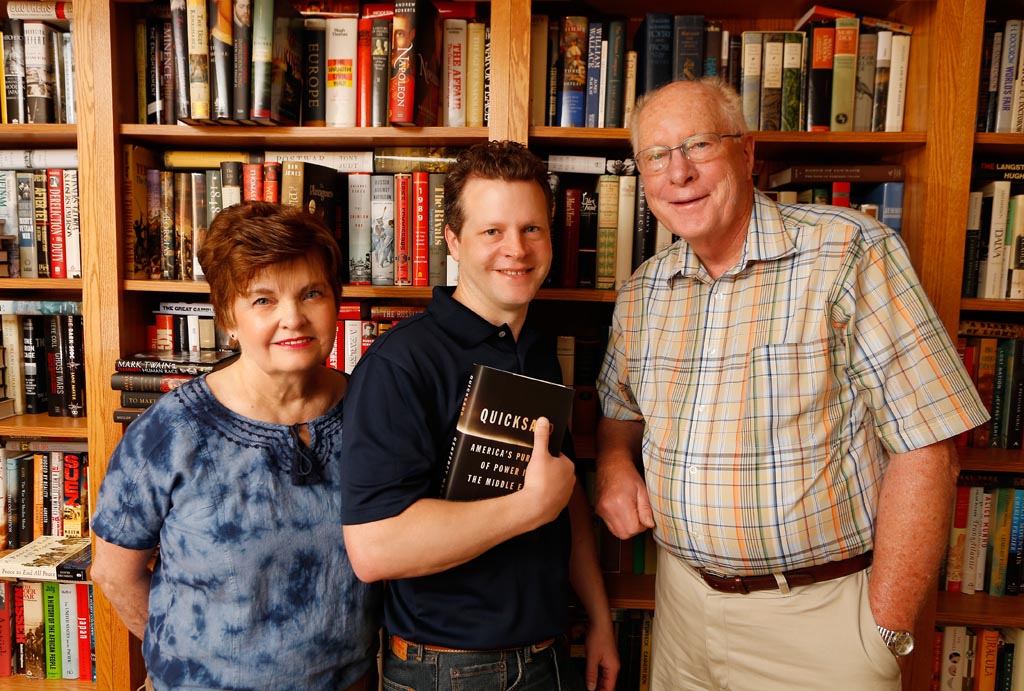

Rowling’s father, Jim, retired about seven years ago after a career at the university’s Calvin T. Ryan Library. As head of acquisitions, the senior Rowling was responsible for overseeing the purchase of books, periodicals and other materials for the library’s collections. His love for books spilled over to his personal life, Chuck Rowling said.

“I grew up in a home that was filled with books. My dad very much influenced me, as did my mom. Our dinner conversations ranged from the U.S. Civil War to current events,” he said.

Rowling’s brothers, both UNK graduates, are also accomplished: Jason is a physician in North Carolina, Matt is a faculty member at Iowa State University.

“I think I always wanted to be a college professor. I would have said so had I been asked back in high school. I witnessed what life was like on a college campus. I saw my dad’s interactions with faculty and students. I love that the college is a place of ideas. I love that our work is focused on building knowledge and empowering students,” he said. “It’s a pretty important job.”

But, he noted, growing up in Kearney, Neb., had its limitations. Rowling had never flown on an airplane until his sophomore year in college. But since then, he’s traveled worldwide, mostly to pursue his academic interests, and he wants his students to have those same opportunities.

“I wanted to learn more about the world and break out of the isolation,” he said.

As a student Rowling took a summer class taught by UNK Professor James Scott on U.S. foreign policy, which included a trip to Washington, D.C., to meet with policymakers.

“The stories that come out of monumental foreign policy decisions – going to war, rescuing hostages – show these decisions are sometimes not deeply considered but instead came from personality quirks or beliefs among the players, but the outcomes have deep significance for all of us,” Rowling said.

A study-abroad trip to France and Belgium, and a summer experience in Côte d’Ivoire, further fueled his interest in political science and closely focused his eye on international affairs, but not before some pretty hardcore experiences with state and national politics.

As an undergraduate, Rowling served an internship in Washington, D.C., for then-Senator Bob Kerrey (D.-Neb.). There, he experienced the energy of Capitol Hill and discovered the importance of constituent services. He also met the woman he would eventually marry, Jennifer (Conner) Rowling. She, too, is a UNK graduate and holds a law degree from the University of Nebraska College of Law.

Rowling also was a campaign field officer for E. Benjamin Nelson’s winning bid for U.S. Senate when Nelson ran to replace the retiring Kerrey in 2000. Rowling loved the boots-on-the-ground aspect of campaigns, and the bug hit again when he was in graduate school, this time in Washington state. There he managed a state legislative campaign, and in 2008 was a field officer for two counties critical to the re-election of Washington Gov. Christine Gregoire.

“I loved the campaigns because I found the strategy of it fascinating, and I wasn’t really ready to give it up in 2008,” Rowling said. “It’s addictive and a constant adrenaline rush where you’re on 24 hours a day. It’s fascinating to engage in politics at a different scale. But it’s a younger person’s game. I’ve got a wife and kids now. I could not in good conscience go back. But I am a campaign junkie.”

Being a campaign “insider” gave Rowling the chance to be directly involved, and also to have an impact.

“You see a different side that you don’t get from the daily news. But the lifestyle is a commitment I can no longer make. And there are a lot of unsavory aspects that make me think I don’t want to do it again. You are selling to your constituents, and you are having to refute misconceptions or lies thrown out by the other side. Today, elections are won or lost via sound bites and clichés, not real issues.

“I felt we were constantly fighting that. So many people are energized by the campaign process. But the nitty gritty of government is less interesting, and disillusioning to voters,” added Rowling. “We don’t always elect the best person to do the job anymore; we are electing the person who best sells himself or herself. The celebrity aspect of politics is inherently harmful and it breeds cynicism.”

With so much experience in American politics, one might think Rowling’s interests would lie stateside, but his research focus has an international twist, which again grew out of his undergraduate experiences.

The study abroad trip to Europe was largely cultural and involved staying with a French family for a week, he said. It was the first time he ventured outside of the United States, and it really opened his eyes. But the three months he spent in Côte d’Ivoire as a research assistant for then-UNK geography professor Laurence Becker was life changing.

Becker needed a student with skills in French language and international affairs, and Rowling had the credentials. The project, titled “Processes of Change in Agricultural Systems: Impacts of Interventions in Ivorian Rice Cropping,” looked at how foreign aid affected the people of Côte d’Ivoire, which is also known as Ivory Coast and is situated in West Africa.

“That experience never left me, and it spurred me to want to learn more about the world,” Rowling said.

The final key for Rowling came in 2002, his junior year, when he won a prestigious Harry S. Truman Scholarship. The award pays toward graduate school and recognizes outstanding students eyeing careers in public service, education or government. It came just before his summer in Africa and cemented his career goals.

Fast forward 10 years and Rowling finished his doctorate at University of Washington after collecting a master’s degree there as well. He was a visiting lecturer at UW-Tacoma and applying for tenure-track positions. Somewhat serendipitously, he learned that there was an opening in his area of expertise, international relations, within the UNK Political Science Department. After a competitive search, Rowling secured the position. He is thrilled to be a colleague with faculty members he so deeply admired and respected as a student; and he is eager to continue the department’s legacy of emphasizing experiential learning through internships and close work with faculty mentors.

Rowling’s teaching and research are intricately linked. He notes that most of UNK’s students are like he was at age 18: eager Nebraskans who are a little bit isolated from the larger world. His goal is to expand that view to help students make a difference. In 2016, he’ll be co-teaching a course with political science professor, William Aviles, on the Israel-Palestine conflict, which will include a 10-day trip to the region. He would like to develop a “civil rights” experiential learning course that would travel to U.S. locales important to the Civil Rights movement. And he involves undergraduates in his research.

Rowling’s research involves working with colleagues Penelope Sheets from the University of Amsterdam and Timothy Jones of Bellevue University. The three focus on political communication, especially how national identity affects how people process and understand U.S. foreign policy and actions.

In 2011, the trio published a study in the “Journal of Communication” looking at how the torturing of prisoners by U.S. soldiers at the Iraqi prison, Abu Ghraib, in 2004 was debated among U.S. political officials and covered in U.S. news media, and how this discourse affected citizen viewpoints about the incident. The scandal, framed by the George W. Bush White House and Pentagon as “un-American,” “isolated” acts carried out by a “few bad apples,” was consistently challenged by Democrats and others, the researchers noted, but competing narratives were largely absent in U.S. press coverage of the story.

A second study, published in 2013 in the “International Journal of Communication,” built on the previous work and looked at press reports and citizen reaction to the deaths of 23 Afghans during a U.S.-led drone strike. The trio’s premise suggested that when people receive what is called “frame contestation,” what lay people might call “both sides of the issue,” people were significantly more likely to be critical of the incident than if they were subjected to just one side of the story. The novel aspect of this research was to look at how Americans viewed stories that were inherently negative to Americans’ self-identity as “good guys” and threaten the image and reputation of the nation.

They note that the White House and military create a narrative designed to protect or preserve national identity; media are reluctant to broach a competing frame; and citizens are unlikely to reject competing frames and instead “rally round the flag.”

The trio looked at what the impact might be if media and others did present opposing views. Through an experiment, different sets of people were exposed to differing narratives regarding the drone strike. The content of the frame and the source were important factors. The team tested two aspects of framing: minimization and reaffirmation. Minimization downplays the gravity of the incident, reduces the scope or size of the incident and blames the incident on low-level flunkies or outsiders. Reaffirmation shifts focus from the incident to other aspects to portray the participants in a more positive manner. In their study, Rowling, Sheets and Jones looked to see whether Congressional comments that differed from White House and Pentagon comments would change citizens’ opinions of drone warfare policy.

Indeed, they did find that support for drone policy was reduced, but party affiliation seemed to also play a role. Republicans were more likely to decrease their (generally positive) level of support for the policy when confronted with competing narratives than either Democrats or Independents. They also found that presenting opposing frames seemed to further erode confidence in Congress regardless of party affiliation, particularly if the contested content revolved around the reaffirmation part of the equation.

The implications, they note, show that media coverage of “more sides” can move the needle of public opinion when the public is challenged to think, evaluate and react to information. They note that citizens are capable of reaching their own conclusions and that media must be willing to report stories that go “against the trend.”

In a recent study published in March of this year, the trio again revisited American opinions regarding what they call “national transgressions.” The most recent work, published in “Political Communication,” looks at the 1968 My Lai massacre in which hundreds of Vietnamese civilians were slaughtered by U.S. soldiers. The team suggests there is a predictable pattern in which nationalism tempers public opinion in group-protective ways.

Rowling said that when these events occur, leaders respond by first minimizing the incident, then “contextualizing” the incident through comments such as “it was a confusing” or the soldiers “were under stress,” followed by “disassociation,” in which leaders state the perpetrators were “bad apples” or “aberrant.” The final stage is reaffirmation in which Americans are reminded of our role as “leaders of the free world.”

The My Lai story distinctly follows this trend, Rowling said. The Nixon administration employed various communication strategies to downplay the massacre, highlighted the strife of warfare, denigrated the soldiers who were involved, and finally worked to bolster and restore national identity. The press acted as an echo chamber, Rowling said, despite strong opposition by some in Congress and the antiwar movement.

The ability to critically analyze U.S. policy that occurred within the remembered past is useful, Rowling said, because it shows that it is not “anti-American” to expose U.S. transgressions to Americans.

“Exposure means we actually live up to our rhetoric,” Rowling said. “It’s the disconnection between our rhetoric and our behaviors and actions that can lead to anti-American beliefs among foreigners.”

That point of view might be controversial in conservative Nebraska. But Rowling believes it’s important for students, particularly students who attend UNK, to have an expanded worldview.

“I may not touch that many students but if I can impact just a few, that’s enough for me,” he said. “You just never know what may happen. I learn so much from my students. If you come in with an open mind, you can learn just as much from them as they learn from you. My challenge is to reach Nebraskans who might have a limited worldview and limited experience and give them the opportunities that were given to me here at UNK.

“Giving them an understanding of why they should care and how all of our actions can cause human suffering in the world is important. I was a student here and my concerns then are their concerns now.”

-30-

Charles “Chuck” Rowling

Charles “Chuck” Rowling

Title: Assistant professor, Political Science

College: Natural and Social Sciences

Education: Bachelor of Arts, political science and history, University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2003; Master of Arts, political science, University of Washington, 2007; Ph.D., political science, University of Washington, 2012.

Years at UNK: 3

Career: Lecturer, University of Washington-Tacoma, 2008-12; Field Director, Chris Gregoire Gubernatorial Campaign for State of Washington, 2008.

Family: Wife, Jennifer; Daughter, Evelyn, 4; Son, Charles, 1.

Hobbies/Interests: Road trips, music, ethnic food, Nebraska football, “Seinfeld”

Interesting Facts: Chuck’s father, Jim, was a librarian at Kearney State/UNK from 1975-2008. He also attended what is now the Child Development Center on campus, which his children now attend.

Areas of research/specialization: Media and U.S. Foreign Policy, Strategic Political Communication, U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East, National Identity and International Conflict; Framing and public opinion.

Courses taught: Introduction to International Relations, American Foreign Policy, International Law and Organizations, U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East, War in World Politics.

Recent Published Articles:

- “The View From Above: A Comparison of American, British and Arab News Coverage of U.S. Drones,” Media, War and Conflict (forthcoming).

- “When Threats Come FromWithin: Cultural Resonance, Frame Contestation and the U.S. War in Afghanistan,” International Journal of Press/Politics (forthcoming).

- “American Atrocity Revisited: National Identity, Cascading Frames, And The My Lai Massacre,” Political Communication, 2015.

- “Frame Contestation In The News: National Identity, Cultural Resonance, and U.S. Drone Policy,” International Journal of Communication, 2013.

- “Some Dared Call It Torture: Cultural Resonance, Abu Ghraib, and a Selectively Echoing Press,” Journal of Communication, 2011.